The Year of Covid: Political religion and the Cultural Wars. Part 2.6. The Utilitarians: the birth of economics as a science.

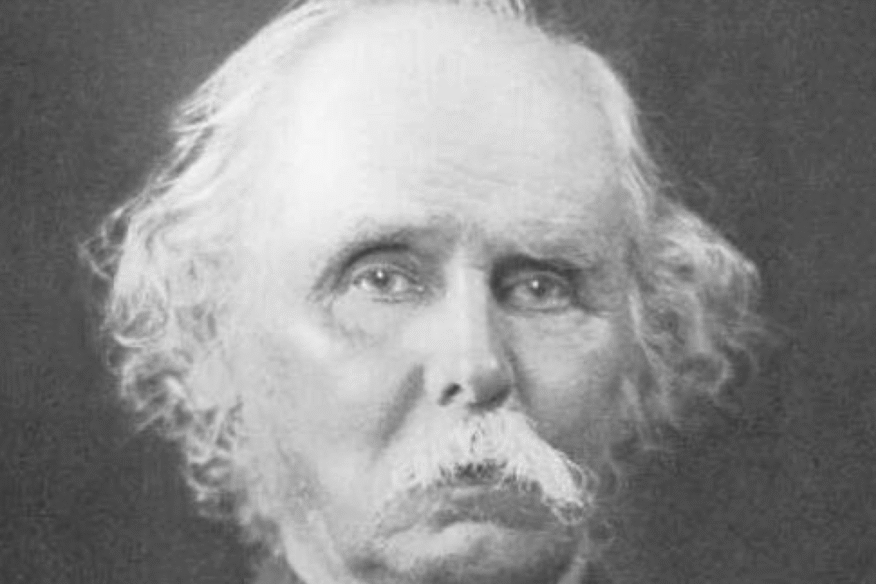

This is the seventh essay in my series on cultural wars: its subject is utilitarianism as the source of the new discipline of economics. It follows on from the previous article, also on the utilitarians, whose central figures are Jeremy Bentham, and James Mill. Both were significant thinkers, particularly on the fields of government and law, the prime focus of both Bentham and Mill. The photo on the front is of Alred Marshall, considered by many to be the founder of modern economics.

In this essay, we continue the discussion about the utilitarians as the founders of economics and sociology. Rather than go through the near two centuries that it took for the field of economics to evolve in the way it is presently understood by highlighting the contributions of each of the prime contributors-Adam Smith (1723-1790), Thomas Malthus 1766-1834), David Ricardo (1772-1823), Karl Marx (1818-1883), the marginalists, Alfred Marshall (1842-1924)- I will cover this terrain , starting with the major movements of ideas and political events during the two hundred or so years, the lives and stories of the prime protagonists, and their ideas in the form of the evolution of a theistic form of natural religion towards secularism, and finally the role of markets conceived as operating in the context of historically conditioned institutions, on the one hand, through to the elaboration of timeless models, unburdened by moral, historical and other extraneous considerations., on the other. We start with a sketch of the two hundred years it took to elaborate the various strands of economics deriving from the original school of utilitarianism.

Europe and the utilitarians 1750-1914.

Over these two hundred years, the political physiognomy of Europe underwent significant changes. In 1750, Catholic and monarchical France was the dominant power, with just under 20% of Europe ‘s total population and economy, compared to under 15% for a divided Germany. Germany had been divided under the conditions of the treaty of Westphalia (1648) to ensure French primacy, as an insurance against a repeat of the destructive Thirty Years War that had engulfed continental Europe in the years from 1618 to 1648. Germany’s divisions enabled French diplomacy to forge alliances among the various states, principalities and duchies into which German speaking Europe was segmented. Unsatisfied with the reduction of Germany, French ambitions to secure hegemony in Europe led to repeated clashes with England, the small, but rising Protestant power on Europe’s flanks. Of the 100 years in the eighteenth century, France and England were at war for 46. .

In 1750, Great Britain, including the four nations of the islands, represented about 5% of Europe’s population of 81 million, but with 10 % of its economy, a per capita income 40% in excess of that of France, and a ten year higher life expectancy. Voltaire visited England in the years 1726-28, admired the Whigs, their habits of religious toleration, and the liberties that explained, in his view, why Sir Isaac Newton and John Locke had achieved such eminence in the nascent physical and human sciences. On returning to France, he determined to present the country as a model to his compatriots. He was followed by Baron de Montesquieu in his visit of 1729-31, who became convinced that the liberties enjoyed by British citizens was due to the division of powers which he observed between the Crown, parliament and the courts. His observation has been hugely influential, but also highly controversial. The historian of law, Boris Mirkine-Guetzévitch wrote about Montesquieu’s observations : “L’Angleterre de Montesquieu, c’est l’Utopie, c’est un pays de rêve »[1]

« England” by the time of Montesquieu’s visit had become in the words of the Union (of Scotland) with England Act of 1707 “United into One Kingdom by the name of Great Britain”. Union was a key policy of Queen Ann, the last monarch of the House of Stuart to be Queen of England, Scotland and Ireland. Wales since the fourteenth century had been subsumed into England. The 1707 Act united the two parliaments into one, maintained a distinct Church of Scotland, a separate legal system and ensured free trade across the island. The merger of crowns and parliament armed Great Britain against the hegemonic ambitions of France. The union created an intellectual, economic, political and military base for a British golden age, culminating in the year 1763, ending the Seven Years War, and leaving Great Britain for a decade the master of both North America and India.

A lead position in this British constellation was held by Scotland, Jonathan Israel writes. “Geographically on Europe’s fringe but central to the eighteenth-century transatlantic maritime system- the major cities – Edinburgh, Glascow, and Abderdeen- … and (its four major) universities had, by the century’s second quarter, acquired an impressive network of reading societies, libraries, periodicals, lecture halls, museums, science cabinets, masonic lodges and clubs. Together these formed a social and institutional basis for an enlightenment predominantly liberal Calvinist, Newtonian, and “design” oriented in character which played a major role in the further development of the transatlantic Enlightenment”[2] The Union, Israel continues, encouraged a rapid widening of (Scottish) horizons, a vigorous expansion of commerce and industry, and served to promote a potent myth that union helped, as Adam Smith wrote in The Wealth of Nations, to deliver “the middling and inferior ranks of people in Scotland” “from the power of an aristocracy which had always oppressed them”. Reform rather than revolution became a leitmotif of the Enlightenment in Great Britain.

This was not to be the case in France. A central theme for utilitarians, in Great Britain as in France, was how to reconcile their two axioms, the inveterate self-centredness of men, and the definition of a good legislator as one who sought the greatest happiness of the greatest number. Claude Adrien Hélvetius (1715-1771), a leading light in the French Enlightenment wrote in his De l’Esprit, which came out in 1758, that “men are not bad; they are merely subject to their own interests”.[3] Given that men “are not bad”, the problem for the legislator is to spread the news that men learn that their own interests are best served by the welfare of the many. “Good laws, he writes, are the only means of making men virtuous. The whole art of legislation consists in forcing men, by the sentiment of self-love, to be always just to others”. [4] In short, the springs of human conviviality are located in the psyche of humans, and not in their geography, climate and culture, as Charles Louis de Montesquieu (1689-1755) argued. The implications of this line of argument are that an enlightened dictator can ensure the general welfare, better perhaps than any democratic legislator; that good laws are always and everywhere the same, because humans are the same the world over; and that utilitarians are inoculated by their crede from racial, national or developmental differences.

François Quesnay (1694-1774) had his Tableau économique published in the same year as De l’Esprit. Quesnay introduces a distinction: in his world, the legislator remains inactive, and men are left to their own devices. Since each man is the best judge of his own interests, the surest way to make men happy is to reduce restrictions that weigh on individual effort and initiative. Governments ought to reduce legislation to the indispensable minimum, allowing- Adam Smith writes “the obvious and simple system of natural liberty” [5] to prosper. Laissez faire in other words is quite compatible with absolute monarchy if the monarch is able to disentangle the institution from the host of vested interests which clings to it. Buried in this optimistic assessment of the human condition is the idea of a natural social order and an assumption of a general science of human nature, whereby humans can improve over the centuries through the acquisition of knowledge, acquired as Locke taught, through the accumulation of experience.

This was the lesson propogated by Anne Robert Jacques Turgot (1727-1781): over time, humanity progresses, Turgot suggests in his Discours sur les Progrès successifs de l’esprit humain , which was published in 1750. Progress over time is possible, despite the fact that each generation has to relearn lessons from the past, by applying the same scientific method to the study of human history as has been used to discover the laws of physics. “ Les signes multipliés du langage et de l’écriture, en donnant aux hommes le moyen de s’assurer la possession de leurs idées, et de les communiquer aux autres, ont formé de toutes les connaissances particulières un trésor commun, qu’une génération transmet à l’autre, ainsi qu’un héritage toujours augmenté des découvertes de chaque siècle; … L’intérêt, l’ambition, la vaine gloire changent perpétuellement la scène du monde, inondent la terre de sang ; et au milieu de leurs ravages, les mœurs s’adoucissent, l’esprit humain s’éclaire ; les nations isolées se rapprochent les unes des autres ; le commerce et la politique réunissent enfin toutes les parties du globe ; et la masse total du genre humain, par des alternatives de calme et d’agitations, de biens et de maux, marche toujours, quoiqu’à pas lents, à une perfection plus grande. »[6]

Jean Marie, Marquis de Condorcet, French philosopher, mathematician, and economist wrote along very similar lines, in his posthumous pamphlet, Esquisse d’un Tableau Historique des Progrès de l’Esprit Humain, published in 1795. Progress in the natural sciences would lead the way to be followed by progress in the moral and political sphere. In this way, humanity was engaged in a voyage of permanent improvement towards a perfectly utopian society. To achieve this, man must unify regardless of race, religion, culture or gender. To this end, he championed the equal rights of the two sexes and of all races. The French Revolution, he was convinced, marked the beginning of a new and glorious era, as the world became an ever more just place, individual freedoms flourished, material affluence grew, and moral compassion spread. Unfortunately, his personal experience did not bear this out: he died in prison, murdered or poisoned as an aristocrat to forego the scandal of publicly executing such a respected figure.

French philosophes and English radicals definitely considered themselves as progressive: but there was little pattern of consistency in their response to the major events of their times. The failed Jacobite uprising in the Great Britain of 1745 fostered in David Hume (1711-1776) a distaste for political enthusiasm and factionalism; Jeremy Bentham supported the loyalists in the American Revolution of 1776; Philip Schofield, a noted Bentham scholar, reports that, in the early years of the French Revolution, the utilitarians were relatively consistent in their defence of the British Constitution on the grounds of the proven track record in promoting the welfare of the country.[7] In 1815, David Ricardo made a financial killing on Napoleon’s fall, but his investment advice was not followed by James Mill, who wrote enthusiastically about unregulated financial markets but did not know them intimately, as did Ricardo; Bentham died in 1832, immediately following the passing of the Great Reform Act that represented the first dent in the monopoly enjoyed by the British aristocracy over the institutions of the British polity, and was followed by the Free Trade reforms of 1846 that further consolidated the growing influence of the manufacturing classes. Tensions among the utilitarians were aggravated by three major developments: Chartism; the Irish famine, and the Anti-Corn Law League.

- The Chartist movement grew out of disappointment among working people at the limited nature of the 1832 reforms. The aim of the Chartists was for working people to gain the vote, and thereby to solve their problems by political means. The movement emerged in 1836, won wide support through their public meetings and pamphlets, and spawned a People’s Charter summarizing their six demands for:[8] a vote for every over 21 year old; the secret ballot; no property qualification for MPs; payment of MPs; equally-sized constituencies; annual parliamentary elections. The movement petered out when the Irish leaders added a seventh demand, to wit the independence of Ireland. In 1867, Disraeli extended the vote to part of the urban working class, and the whole programme, except for the sixth demand, was enacted by 1918.

- The direct cause of the Great Famine in Ireland between 1845 and 1847 was the crop failure of the potato, on which one third of the population of 8 million depended for food. Rain, writes Halévy, “rotted all the tubers not already dug up”. Famine stalked the land. What was to be done? Commentators, Irish and British, proposed the consolidation of small plots; but that was no answer to the urgency of the moment; nor were public works, such as drainage of the bogs in central Ireland; free trade, said Irish MPs. But as Richard Cobden, the arch free trader, said in the Commons:, Ireland was the least likely part of the United Kingdom to benefit by withdrawal of tariff protection, “for Ireland had not, as England had, the means of finding employment for her agricultural population in her manufacturing districts”[9]. By 1851, the Census recorded a population of 6.6 million, the decline being attributed to death or to emigration. Halévy writes: “When all is said and done, the recovery of Ireland was due not to government action, subsidies, or the inauguration of public works, but to the free sale of Irish cattle in the English market and the voluntary emigration of Irishmen to Australia and America”.[10]

- The Corn Laws had protected British corn markets from competition through a sliding scale mechanism since the end of the Napoleonic wars. Utilitarians had mobilized in opposition as part of their campaign to reduce the powers of the aristocracy, and as Bentham became converted to the idea of universal suffrage as the only way to ensure reforms. An Anti-Corn Law League had begun agitating for repeal, and helped to establish The Economist in 1843 – a journal that became a permanent voice in favour of utilitarian causes on the British media landscape. But it was the Great Famine which triggered the political manoeuvrings which led Sir Robert Peel, the Tory leader, in early 1846 to take the dramatic step to repeal protection. One of the arguments in favour was that the problem in Ireland was the price of corn not the quantity available. The measure led to splits in the previously protectionist Tory party, and a longer term realignment of party politics. By 1859, the Peelites had merged with the Whigs and the Radicals (the utilitarians) to form the Liberal Party, under the leadership oif William Ewart Gladstone. The Tories regrouped under the leadership of Benjamin Disraeli, giving rise to the distinct party political configuration of Great Britain in the fifty or so years prior to 1914.

Class and ideas among the utilitarians 1750-1914.

The leading lights of the utilitarian movement were in general men of leisure-very rarely women- enjoying university careers, men of the cloth such as Thomas Malthus (1766-1834) , wealthy business men-very wealth in the case of David Ricardo, or heirs to solid inheritances, as in the case of Beatrice Potter, better known as Beatrice Webb (1858-1943) , one of they key figures with her husband Sidney (1859-1947) of the early Fabian movement. Adam Smith, considered to be the father of economics, told the story of David Hume meeting the nightwatchman, Charon, ferryman across the river Styx, to Hades. Hume asked for a few more years of life. “You lazy, loitering rogue, countered Charon…get into the boat instantly”.[11] Charon of course was notoriously indifferent to whoever asked for his services, monarchs or mendicants. But he was selectively appreciative of utilitarians: they all lived well into their mid-late 60s, until the 1880s when there was a general uptick in longevity due to better nutrition, hygiene, housing, sanitation, control of infectious diseases and other health measures. By comparison, life expectancy for working people around the mid-eighteenth century was well below 40 years, moving slowly up to just over 40 years of life at the time of the end of the Napoleonic wars, to rise to 45 to 50 years by 1901. The Webbs both died in the 1940s well into their eighties. It is thus safe to state that the theorists of utilitarianism were from the upper class, ancestors of modern champagne socialists, not at the pinnacle of society then occupied almost exclusively by the aristocracy, but with a life expectancy in excess of 30 years longer than the average working man. Radicalism in England sang with an upper class accent.

Upper class but not uniformly wealthy. David Hume’s family finances were “slender”, until after twelve years of hard work, he produced his six volume History of England, published over the years from 1754 to 1761, became a best seller, made him a wealthy and famous man, and gave him the independence he craved. This had not been the experience of his first book, A Treatise of Human Nature, which he, and many others, considered his best book, but “fell, as he wrote in his Autobiography, dead-born from the press”. [12] The book gave him an early reputation as an atheist, at best a deist, and barred his route to a university chair. Another star in the Scottish Enlightenment,Adam Smith, best known for his major work, An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations, which came out in 1776, was befriended with Hume, but steered clear of being tainted as atheist. He lived out his later years in comfort from the generous revenues he received as commissioner of both customs and salt for Scotland, topped up by the patronage he enjoyed from the Duke of Buccleuch. Thomas Malthus, described by John Maynard Keynes,”as a gentleman of good family and independent means”, [13] was a cleric of the Church of England, and appointed a Professor of Political Economy at the East India Company school at Hailebury. David Ricardo became immensely rich in his own right, making sound bets on the bond markets during the Napoleonic wars, while Karl Marx married Jenny von Westphalen, an heiress of the lesser German nobility, and lived off her inheritance for the rest of his life. Alfred Marshall was a Cambridge University man all of his professional life, while Beatrice Webb, inherited a substantial annual sum in her father’s will, which enabled the Webbs to live off their writings, and to eventually enter the pantheon of the Labour party’s establishment through inter-marriages of numerous nieces and nephews. Socialists may deplore inequality, but they definitely prefer not getting on the wrong side of it.

The major protagonists of utilitarianism were consistent about religion: they were uniformly skeptical. This should come as no surprise: David Hume championed empiricism. He definitely did little to ingratiate himself with the ecclesiastical authorities of his native Scotland. In his dissertation of 1757, entitled The Natural History of Religion, he argued that monotheism derives from polytheism and that religious belief derives from dread of the unknown. Adam Smith took a different tack: he drifted away from his beloved mother’s deeply held Christian beliefs, and publicly signed on to the Calvinist Confession of Faith, in order not to shock her, but also to assure that he could find gainful employment as a professor at Glascow University. Bentham became alienated in early years from the Church of England, and embraced a vigorous atheism. His friend, James Mill had trained for the Scottish Presbyterian ministry, but as his son, John Stuart Mill recorded in his Autobiography, his father “ had, by his own studies and reflections, been early led to reject not only the belief in Revelation, but the foundations of what is commonly called Natural Religion”. [14] James, John Stuart continued, “taught me to take the strongest interest in the Reformation, as the great and decisive contest against priestly tyranny for liberty of thought.” David Ricardo, James’ friend and collaborator, was equally open minded: he had attended the rabbinical school in Amsterdam, then broken with his father’s Jewish faith, married a Christian and become a Unitarian, a non-Trinitarian faith that became extremely influential in Victorian England. His growing interest in matters economic had been stimulated by his reading of Adam Smith’s Wealth of Nations, and in particular by his experience as a stockbroker. He first broke onto public attention as an author of a set of influential articles on monetary policy and inflation.

By the mid-nineteenth century, those who militated on the more radical end of the political spectrum felt less compunction to identify as Christians. This was particularly so for Karl Marx, who descended from a long line of rabbis, but whose father had converted to Protestantism in Prussia, espoused the ideas of the Enlightenment and expressed interest in the ideas of Kant and Voltaire. Marx, fils, married in a Protestant Church, but his ideas developed in a different direction, and he became a militant atheist: “criticism of religion, he wrote in A Contribution to the Critique of Hegel’s Philosophy of Right, (1843) is the prequisite of all criticism”. The other major figure of the mid-century in Great Britain was John Stuart Mill: “ I am, he writes in his Autobiography, … one of the very few examples, in this country, of one who has not thrown off religious belief but never had it”. Two major protagonists of what came to be called “liberalism” in Great Britain, wore their religion lightly: Richard Cobden militated for free trade, against war, for the extension of the suffrage and for liberty of conscience was a member of the Church of England; John Bright was a Quaker, spiritual heirs to Cromwell’s troops who believed that their failures had been a punishment by God for their resort to violence in the civil war. Herbert Spencer gained notoriety as an agnostic, coining the Darwinist phrase, “survival of the fittest”, but sought in First Principles (1862) to establish the idea that both science and religion can agree that human understanding is only capable of relative knowledge. A fellow Darwinian agnostic, Thomas Huxley, described the principal of agnosticism whereby “it is wrong for a man to say that he is certain of the objective truth of any proposition unless he can produce evidence which logically justifies that certainty”.[15] The scientific method, in other words, had to be applied to all disciplines, including theology.

It is worth recording what a radical idea this was. In his article on “Religion, the State and Education in England”[16], James Murphy writes that “it was inevitable that from the beginning of the Christian era in England education would rest in the hands of the Church.” Conflicts between Church and State were rare, he records, in the centuries preceding the Reformation, but the split with Rome under Henry VIII prompted efforts to impose uniformity of beliefs on England and Wales, that lasted until the late eighteenth century, when laws preventing Nonconformists and Roman Catholics from teaching were repealed. They had in any case been largely inoperative, but had fueled inter-denominational political warfare over matters educational. Two factors pushed the State to play a greater role: one was the success of non-partisan state promotion of popular education in the United States, Holland and Prussia. The result in England was a creeping barrage of state measures during the early nineteenth century, such as the funding of buildings, the formation of teacher training colleges or the creation of a school inspectorate. Another was the extension of the suffrage in 1867, which led to a broad parliamentary consensus that it was necessary “to compel our future masters to learn their letters”.[17] The 1902 Educational Act extended further State influence over denominational schools, although by then inter-denominational rivalry over education was arguably on the wane as religious beliefs and church attendance began to taper off. Toleration to religious differences had already seeped into the body politic: Thomas Malthus, though an Anglican divine, had attended a dissenting academy; Cobden and Bright co-operated across the denominational divide on free trade; eyebrows were raised when clerical rules in St John’s Cambridge, obliged Marshall to resign from his lectureship on marrying. As Beatrice Webb observed, “that part of the Englishman’s nature which has found gratification in religion is now drifting into political life.”[18] The death of God, in short, began to burden politics.

Ideas have always been attracted to politics, like moths to light. Enlightened Europeans sped to Scotland’s four universities and salons in the eighteenth century, and visits were reciprocated. One channel was to join the diplomatic corps in secretarial capacity: that was David Hume’s route, first at the courts of Turin and of Vienna, and then as secretary at the Paris Embassy, where he met Rousseau. Adam Smith travelled with the young Duke of Buccleigh to France where he met Voltaire, and Benjamin Franklin and became acquainted with the Physiocrats, one of whose leading lights, Quesnay, we have met. Quesnay is remembered as the father of “laissez faire”. Smith clearly had his reservations on “laissez faire”, as will be clear when we discuss Smith’s subtle understanding of the role of politics in markets. As he wrote in The Wealth of Nations, Smith instead had written that the system of the Physiocrats, ‘with all its imperfections, is, perhaps, the nearest approximation to the truth that has yet been published upon the subject of political economy’.[19] Arguably, the most adamant of free market economists were not the heirs to Adam Smith, but the French journalist Frédéric Bastiat (1801-1850), who understood the basic insight of Edmond Burke’s Reflections on the French Revolution, that abstract ideas applied literally to the historically inherited condition of humanity invariably yields circumstances that Bastiat called “unseen”, in other words “unintended”. This was an insight overlooked by utilitarians of the late nineteenth century, “the new liberals”, as they called themselves, mightily impressed by the government actions of Germany’s Iron Chancellor, Otto von Bismarck. One of those government actions was to bring universities firmly under political influence. In Great Britain, the German university’s influence came to rest more in the new universities, more influenced by utilitarianism, than were the old clerical universities of Oxford and Cambridge. As one wit expressed it, Professor Nebel (Professor Fog) taught in the University of Dummerjungenberg.[20] Wiser minds, apparently, had a better chance of prevailing in Great Britain.

In his six volume history of England in the nineteenth century, Halévy realized that the liberal interlude of the mid-ninetenth century was passing. He took up the narrative in 1895: “I did not find it easy to decide where I should end my narrative”. Should it be in 1901, the year of Queen Victoria’s death? The conclusion of the Boer war the year later? 1906 when the Liberal Government of Asquith, Lloyd George and Churchill was elected? or should the series be ended in 1914, and the outbreak of the world war? The whole period between 1895 and 1914, he wrote, did not really belong to the English nineteenth century. These were years of decadence, when there was a sense that the vitality of mid-century England was on the wane, when “ we witness the decline…of the ideal which (England) had pursued for an entire century and which she had come to regard as the secret of her greatness-the decline of that individualist form of Christianity in which Protestantism essentially consists…”, and the spread of neo-Catholicism and of socialism. He could have added the seeds sown also of a burgeoning government, and of left-wing anti-semitism, both promoted by utilitarians. “The task to which I am impatient to return and to which I propose to devote the remainder of my strength and my life will be the story of that great epoch(-the middle years of the century) during which the British people cherished the splendid illusion that they had discovered a moderate liberty, and not for themselves alone but for every nation that would have the wisdom to follow their example, the secret of moral and of political stability”. [10] Those middle years are covered in an unfinished volume, edited by R.B.McCallum, entitled Victorian Years: 1841-1895. [21]

From natural religion to secularism.

There were many rivulets that ran into the broad stream of theistic natural religion in eighteenth century Great Britain. One such rivulet is Bishop Joseph Butler’s Analogy of Religion, Natural and Revealed (1736), which Will Durant describes as remaining “for a century the chief buttress of Christian argument against unbelief”.[22] The book’s broader importance is that the good bishop’s thinking impressed itself enough on Hume for both to agree that religion was not readily susceptible to reason. Nature, Butler observed, “is a mess of riddles”, and “we cannot expect revelation to be any clearer”. Writing two decades later, Hume as good as plagiarises the same thought: “the whole, his writes in his The Natural History of Religion, is a riddle, an enigma, an inexplicable mystery”. [23] Neither statement, it is safe to say, was a full-hearted endorsement of religious tenets, but neither were they a denial that faith could take over where reason left off. Indeed, both statements set the bar of proof incredibly low, reason and revelation being equally unhelpful. Adam Smith, more of the pragmatist, avoided the morass, and appealed to the tolerant midde-ground of enlightened Presbyterianism. The “Great Architect of the Universe”, in Smith’s expression, looks after the macro-side of things, Nature and the World, while man is allotted “ a much humbler department”, “the care of his own happiness”. [24] This appeal to God, whether personal or not, enables Smith to bring Providence into his theory of the social order. His is not a materialist approach. His target is mercantilism, an artificial creation, which was well written up by Sir James Steuart Denham, a Scottish baronet, in Inquiry into the Principles of Political Economy (1767), a book that Smith did not mention in The Wealth of Nations, in order to give it no publicity. Smith’s natural theology conceives of an all-wise Being who directs all the movements of nature, such as to maintain the requisite amount of happiness. The Divine Author ensures that the moral and physical world are brought into alignment though the simplicity, harmony, order and equality that permeates his own being. Do away with artificial creations, and Nature flourishes. This is what Smith means when he refers to the “invisible hand”, mentioned in both Moral Sentiments and The Wealth of Nations. The pursuit of individual self interest and of the public welfare are brought into harmony by the benevolence and the workings of the “invisible hand” . Providence, to put Adam Smith words into the bureaucratic mouth of the OECD of 1977, when it cooked up the phrase, is engaged in the “adjustment process”. By that time, secularism had long since banished Providence from market shake-outs.

David Hume once said that the best theologian he had met was an old lady who saw him floundering in a pond into which he had erred, and said “Do you believe in the Saviour, Jesus Christ”, to which Hume nodded assent, whereupon she did her Christian duty and helped to pull him out. The story illustrates the gap that pertained for much of our two hundred years between the skepticism of the few, attracted to the latest ideas, and the rural many who continued to believe in a magical natural world, governed by supernatural powers, far in excess of what humans could order. Great Britain remained a Christian country, divided to be sure between the Anglicans, the various strands of non-conformists, and the Catholics, largely from Ireland. Things were never static however. The 1851 census produced shocking news, that in most large towns fewer than 10% of inhabitants attended a place of worship on Sunday. Churches responded by developing charitable activities, and church building boomed. The Jews were the only sub-national non-Christian faith, numbering 60,000 in the 1880s and expanding to 300,000 by the outbreak of the war-an increase accounted for by the influx of refugees from the anti-semitic purges which broke out in Tsarist Russia. In Halévy’s uncompleted book on The Victorian Years, he maintains that the Church of England was not burdened by a ”bulky theology”, had moved with reforming times, joined the campaign against slavery, and was united with other Protestants against Roman Catholicism. The eighteenth century lingered on well into the nineteenth, exemplified by Hugh Percy, Bishop of Carlisle, and nephew of the Duke of Northumberland, who travelled up to town driving the four horses of his mail coach himself. He died in the 1840s, by which time the doctrine of Free Trade was on the way to becoming a public theology. Marx’s predictions of revolution turned out to be wildly out of line with reality: rather the stern face of law and order became over time associated with the figure of the unarmed “peeler”, the bobby on the beat ensuring that the streets remained peaceable. The reasons for that peacefulness may be illustrated by one of Gladstone’s major speeches: your enemies, he told his working class public, will teach you to look to the legislature to better the radical evils that afflict human life. They seek to delude you. “It is the individual mind and conscience, it is the individual character, on which mainly human happiness or misery depends” (Cheers). “The social problems that confront us are many and formidable. Let the Government labour to its utmost, let the Legislature labour days and nights in your service, but after the very best has been attained and achieved, the question whether the English father is to be the father of a happy family and the centre of a united home is a question which must depend mainly upon himself”. [25]Hard work, discipline, a shared view of right and wrong, self reliance and foresight-those were the virtues that made England prior to 1914, not government largesse and political shenanigans. “Until August 1914, the historian A J P Taylor writes, sensible law-abiding Englishmen could pass through life and hardly notice the existence of the state, beyond the post office and the policeman”. [26]

Englishmen lived liberal economics; but Frenchmen helped develop it. That was particularly the case in the eighteenth century, when enlightened Frenchmen took England as a model, admired its relative toleration (while forgetting that 220 crimes were punishable by the death sentence), and proposed “laissez-faire” as the best alternative to a centralized and Catholic monarchy. Revolution came, and with it-as Edmund Burke predicted-one unexpected surprise after another. The pattern of events is well illustrated in the career of the aristocrat Claude Henri de Rouvry de Saint-Simon (1760-1825). He fought at the battle of Yorktown with George Washington; became an ardent revolutionary at home; nearly lost his head in the Terror; tried his hand at marriage and failed; became interested in science as a new form of religion; made friends with Auguste Comte, the father of positivism- a doctrine which states that metaphysics – the study of why- is a waste of time because -as Butler and Hume observed, there is no answer- while science describes and advances our knowledge about the why. Humanity needs no more, the positivists aver.

Saint-Simon also learnt about entrepreneurs from the liberal economist, J.B. Say as possessing out-of-the-ordinary co-ordinating abilities. [27] Science and entrepreneurs, Saint-Simon concluded in his later years, should embrace a “new Christianity”, stripped of its Catholic and Protestant excrescences, that would focus on satisfying the material and spiritual needs of all people.[28] This new Christianity would not obscure science, but would be vital to politics, in the sense that paradise would be located not in the hereafter, but in this world. The messenger of this world would not be the Christ but the poorest of the poor. “Real Christianity commands that all men behave as brothers to others”. This Saint-Simonian amalgam of entrepreneurship, free markets and elitism reached its zenith under the reign of Napoleon III (1852-1870), but was interrupted by the Prussian victory in the war of 1870, leading to the collapse of the second Empire and the constitution of the Third Republic. The leadership of continental Europe slipped to Bismarkian Germany, its corporations and banks, its high culture, its nascent welfare state, and not least the emergence of mass politics, exemplified in the Marxist Social Democratic party.

A component of the growth of secularism in the nineteenth century was a belief that man was good, and could flourish, as Rousseau argued, if released from his chains. He was not condemned, as Saint Augustine, had taught, to live in sin, to find salvation only through the agency of Christ, and forever to endure the blows of this world, until rewarded in the hereafter for his patience and sacrifices. Marx ridiculed this view, and wrote in his article “Zur Judenfrage”, published in 1844 in a one-off publication, Deutsch-Französicher Jahbücher, that the “Jewish problem” could only be resolved by dissolving the Jewish and Christian religions. This would end the ghetto into which Christians had herded Jews as money lenders- because charging interest was considered sinful, something Jews could do, but not good Christians. In the ghetto, Marx implied, Jews were interested only in “huckstering and money”. Ending the physical ghetto was not enough; the ghetto was religion. Abolishing it would reveal problems that needed resolution, such as inequality and the exploitation of labour by capitalists. [29]

There were of course other major challenges to religion, including the application of the historical method to the study of the Bible; the study of geology, and the study of biology. The first undermined the simple belief in a Bible written by the hand of God, to make way for a more nuanced view of the Bible as a collection of stories built up over millenia, some in the form of genealogical trees; others of histories handed down by word of mouth over the millenia, and gilded in the process; and yet others, such as Genesis which is an account of the origin of the material world, in which God inserts ethics. The study of geology vastly extended human understanding of the immensity of time and space : Charles Lyell, for instance, in Principles of Geology, which made a sober presentation of the Earth’s age, and revealed that that the biblical interpetation of the world’s origins was not factual. Charles Darwin devoured Lyell’s book, and fed its ideas about evolution into his The Origins the Species, which came out in 1859. Origins was an even more deadly blow to fundamentalist interpretations of the Bible, on which Protestantism had come to rely.

The new campaign against religion originated in “Socialist” circles. Halévy dates the opening salvo not in Marx’s essay on “the Jewish question”, but on George Jacob Holyoake’s foundation in 1846 of the weekly The Reasoner. Under the influence of the revolutionary movements of 1848, the title page was changed to A Weekly Journal, Utilitarian, Republican and Communist. Bentham was a suitable patron, given the violence of the pamphlets that he had published thirty years earlier. His successors, though, were more careful to avoid frontal attacks on religion or Christianity. “To present positivism in open conflict with religion of any kind”, J.S.Mill wrote to Auguste Comte, “is perhaps the one way of presenting it, which, in my opinion, it would be most inopportune to employ in England today. Under existing circumstances , I believe, those who write for the English public should say nothing about religion, while making as many indirect attacks on religious beliefs as they have an opportunity to make”. [30] This of course was exactly the same approach as the Fabians applied from the 1880s onwards to the transformation of the market system and of “society” by indirect action, permeating the élites with their socialist ideas.

The last fifty or so years of the century prior to 1914 were thus notably different to the early nineteenth century, when a happy coincidence occurred which enabled the militancy of religious belief in the shape of Methodism, to ally with the very different militancy of the utilitarians to merge into a liberal reform movement, of which Halévy became the historian. The alliance had world-wide importance; it installed in Great Britain and in Ireland a deep belief in parliamentarianism; it won over the older Great Britain to the cause of anti-slavery; by British efforts, the anti-slavery movement became a world-wide cause; the alliance created the conditions for Britain’s second, and liberal Empire, from which modern India and the Dominions sprang. It charted a very different path from the Prussia that had been Great Britain’s prime ally, with the Hapsburg monarchy, in the defeat of Napoleon; and it contrasted significantly from the turbulent history of France, which swung from Directory, to Empire, to monarchy, and to parliamentarianism unchecked by the dualism of Great Britain’s mid-century formula of the Crown-in-Parliament, that lent continuity and legitimacy to the affairs of Whitehall and Westminster.

Utilitarian economics.

Utilitarians are best known as dry-as-dust bores, who invented a discipline which has been labelled “the dismal science”. Charles Dickens’ character Oliver Twist is known for his exposé of workhouse abuses made topical by utilitarian Poor Law Reform. In Hard Times, Dickens presents Mr Gradgrind, headmaster, who names his sons Adam Smith and Malthus Gradgrind. Gradgrind’s educational philosophy amounts to the statement that “in this life, we want nothing but Facts, sir, nothing but Facts!”. Everything is square about him, his coat, his legs and his shoulders. Yet Gradgrind suffers and eventually condones the practice of charity. Which is the utilitarian Gradgrind, then? One camp considers Bentham’s followers, on government, law, or politicsand economics as hard, inhumane, inflexible, and tyrannical. The other maintains that a “broadly Benthamite capitalist, and liberal age in pursuit of utility alike in commerce and industry and in socio-economic political reforlms, in good measure favourable to freedom and levelling in terms of class and gender”.[31]The answer to this question is both, and, but inconsistent.

The first on-going debate among utilitarians is the respective role of government and markets. Adam Smith fails to mention Sir James Steuart Denham, author of Inquiry into the Principles of Political Economy, in The Wealth of Nations. But the baronet is always present in its pages. Both Steuart and James Mill, Bentham’s friend, hail from families which backed the Stuart dynasty. Mercantilism was in the Stuart blood, and Steuart Denham, pens his treatise in favour of active government policies of export subsidies, price supports for agriculture, or tariffs in defence of higher local wages. Adam Smith’s counter is immediately to introduce his central idea of the division of labour: “it is the great multiplication of the productions of all the different arts, in consequence of the division of labour, which occasions, in a well governed society, that universal opulence which extends itself to the lowest ranks of the people”. [32] The larger the market, the greater the division of labour, the richer the population. The more protection, as is “the policy of Europe”, the greater the hindrances to prosperity. If governments withdraw, nature takes over and delivers via “the freedom of trade, without any attention of government…(that supply of ) the wine which we have occasion for…”. Every individual in pursuit of their own gain, is “led by an invisible hand to promote an end which was no part of his intention”, the welfare of the whole. This idea is expressed in his famous statement: “It is not from the benevolence of the butcher, the brewer or the baker that we expect our dinner, but their regard for their own interest”.[33] “I have never known much good done, Smith adds, by those who affected to trade for the public good”. [34]

In this view, the government is requested to reduce its activities to security, law and order, public works and “measures for facilitating the commerce of society.” This is the story told by David Ricardo, demonstrating that countries with differing domestic costs and prices could trade to the benefit of each other. But government was not an abstraction, so much as a living stake in the nation’s political battles. The year 1846 , when tariffs on corn were cut, was preceded by a titanic political battle, and required a functioning and effective government to impose what were in effect highly controversial measures. Utilitarians were for ever torn about whether it was right to let markets rip, as Jeremy Bentham did in his no-holds barred pamphlet In Defence of Usury, (1787) or to conquer government power in order to implement their policies. The sweet spot where voting rights were restricted, and government was powerful, came between 1832 and 1867. Disraeli’s extension of the suffrage that year created heart-burns that proved enduring: could working people be trusted with the vote? Did they have the right sort of knowledge? Would they not clamour for ever wider powers to government? In his second version of The English Constitution, Walther Bagehot, editor of utilitarianism’s prime public voice, The Economist, is clearly concerned. “In the communities where the masses are ignorant but respectful, if you once permit the ignorant classes to begin to rule, you may bid fareful to deference for ever. Their demagogues will inculcate, their newspapers will recount that the rule of the existing dynasty (the people)is better than the rule of the fallen dynasty (the aristocracy)”. The optimum balance between government and markets, in other words, was when a few, including enlightened utilitarians, ran the country, and the plebs were kept at bay. They have never lost their nostalgia for those golden years. Free trade is their theology, unto which all type of good things happen to those who embrace it, such as peace and brotherly love.

The sentiment was very present in the Natural theology of the eighteenth century. God, as it were, was a nice chap. “All systems, Smith writes at the end of Book Four of The Wealth of Nations, either of preference or restraint being completely taken away, the obvious and simple system of natural liberty establishes itself of its own accord.” [35] Jacob Viner places Smith’s theology centre stage in his interpretation of the idea of “laissez-faire”. [36] Smith’s theme, says Viner, is that economic phenomena are manifestations of an underlying order in nature, governed by natural forces, and requiring a system of natural liberty. Not everything is perfectly harmonious, of course; we are not in the Garden of Eden, to speak with the Book of Genesis. There is conflict, for instance between masters and workers over wages; merchant seek profits, customers low prices; entrepreneurs plot to raise them. But laissez-faire will sort things out better than the clacque of self-interested aristocrats feeding off the public trough called government. Nature is a beneficient regulator. The French Physiocrats said so. The Whigs liked to think so. Then, to the surprise of English optimists that 1789 was a replay of 1688, came Robespierre’s war on religion, the reign of terror, and twenty years endless war. By 1815, this cheerful view of human affairs, and of God’s part in them, proved more problematic to defend.

There is no need to venture out of the domain of academic ideas to find evidence that grimmer concepts about Nature were beginning to take hold. Thomas Malthus, in his An Essay on the Principle of Population, (1798) argued that it was not a good idea to herd people into large cities, where they bred like rabbits. Keep them back in the countryside under the supervision of squire and parson, and their natural propensity to copulate could be regulated. The point was made politely: “Yet in all societies, even those that are most vicious, the tendency to a virtuous attachment [i.e., marriage] is so strong that there is a constant effort towards an increase of population. This constant effort as constantly tends to subject the lower classes of the society to distress and to prevent any great permanent amelioration of their condition. » [37] The power of population, writes our cleric, rises geometrically, while the output of agriculture only rises arithmetically. Sooner rather than later, famine strikes the poor; the population plummets; scarcity of labour raises wages; the good times return, wages rise, babies are born galore, and so on in unending cycles. Demography is the deus ex machina. Ricardo placed this Malthusian cycle at the heart of his argument for comparative advantage, and added a new dimension of class war, which Marx latched on to. According to Ricardo, landowners benefitted in the Malthusian cycle as the demand for food rose, and abundant population ensured wages fell. So free trade in corn had to be introduced to save the poor, keep wages for manufacturers low, and make food cheap through imports. One of the unintended consequences of Free Trade in 1846, was to massively lower the prices of food imports from the Americas in the 1880s as long-distance transport and refrigeration technologies developed. This devastated the economics of the Britain’s still dominant class and opened the trans-Atlantic marriage market for American heiresses to bring finance to the rescue of the British aristocracy. Like true progressives, utilitarians stumbled from one unintended consequence of their actions to another.

By the mid-nineteenth century, the idea of a beneficient Nature gave way to a growing conviction that Nature was malevolent. Marx and Engels as utilitarians[38] based their whole system on class war, and Darwin named his book, On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection(1859) . In March 1883, at the graveside of his friend, Marx, Engels famously said, “ Just as Darwin discovered the law of the development of organic nature, so Marx discovered the law of the development of human history”.[39] That law was announced in the opening lines of the Communist Manifesto of 1848. “The history of all hitherto existing society is the history of class struggles”. The thesis of the Communist Manifesto is summarized by Engels in the third edition of The Manifesto: “The fundamental proposition of our joint production is: “That in every historical epoch, the prevailing mode of economic production and exchange, and the social organization following from it, form the basis upon which is built up, and from which alone can be explained the political and intellectual history of that epoch; that consequently the whole history of mankind (since the dissolution of primitive tribal society, holding land in common ownership) has been a history of class struggle, contests between exploiters and exploited, ruling and oppressed classes. That the history of these class struggles forms a series of evolutions, in which, nowadays, a stage has been reached where the exploited and oppressed class-the proletariat-cannot attain its emancipation from the sway of the exploiting and ruling class-the bourgeoisie- without, at the same time, and once and for all, emancipating society from all exploitation, oppression, class distinction, and class struggles”. That emancipation consists in victory in the class war through the abolition of property, and with it, the abolition of heredity, family and nationality. This is the heart of the communist programme.

We are back to Hobbes’ « bellum omnium contra omnes ». Nature is savage, not nice. Engels writes in an unfinished manuscript, The Dialectics of Nature, that “Darwin did not know what a bitter satire he wrote on mankind, and especially on his countrymen, when he showed that free competition, the struggle for existence, which the economists celebrate as the highest historial achievement, is the normal state of the animal kingdom. Only conscious organization of social production, in which production and distribution are carried on in a planned way, can lift mankind above the rest of the animal world as regards the social aspect, in the same way that production in general has done this for men as a species”. [40] What we are describing is that amalgam of Marx and Darwin, called social darwinism. We are not talking about competition as meant by utilitarian economists; we are talking about the theory of natural selection which teaches that in the animal and plant kingdom the weak succumb and the strong triumph. Thucydides made the point in his account of the Melian dialogue in the course of the Pelopenesian War (431-404 BC) : “the strong do what they can and the weak suffer what they must”. This is the language of power politics, and a harbinger of the twentieth century.

There is one more major strand in the development of utilitarian economics prior to 1914. The emergence of neo-classical economics, as it came to be called, in the marginal revolution of 1871-74, and its concomitant claims to be even more scientific than its predecessors, the classicals- that is, the economics of Turgot, Smith, Malthus, Ricardo, Bentham, Mill and John Stuart Mill, Marx and Darwin. All of these had their own preferred way to resolve the fundamental utilitarian dilemma-self-interest versus public welfare-Smith proposed sympathy whereby entrepreneurs can read into other men’s minds; Malthus proposed a cycle of famine and plenty; Bentham and Mill believed in the power of elites to convert the lesser among us to their ideas; Ricardo proposed free trade to escape the Malthusian cycle of plenty and famine; J.S. Mill’s ethics bubbled down to not harming others, not a very complete answer to a world where Nature can no longer be invoked as benign; Marx proposed violent class war, ending on bloody revolution, followed by heaven on earth; and Darwin suggested that the Law of Nature was selection of the fittest.

With the marginalists, we suddenly find ourselves sailing in calmed waters. This was not because the marginalists of the early 1870s wonted in radicalism: they aspired to get more scientific, closer to how physical sciences operated. So they decided to strip all the noise from discussion of how markets worked: God, ethics, culture, history, institutions, government, inequalities, even personal tastes, budgets and technology. Marginalism brings utilitarianism to the individual, and suggests that the core of economics is about the choice consumers make in the decision to purchase one extra unit of good or service relative to the additional utility they will receive from it. As Mark Blaug writes in his Economic Theory in Retrospect, “for better of for worse, …economic theory in the period 1870-1914 consisted almost wholly of static microeconomics based squarely on the equimarginal rule”- the rule whereby the consumer choses a combination of goods to maximise their total utility, in other words the marginal utilities of goods to price. We are moving from high drama to the breakfast table, from forms of macro-economics to relentless study of micro-economics. The marginalists thus introduce, Blaug suggests, three key changes in utilitarian economics: the shift from the classicals’ focus on growth through the division of labour and evolution of the economy, to a focus on allocative efficiency; the dominant role of substitution at the margin opens the door to explicitly mathematical reasoning; values in the factors of production-land,labour, or capital-are all calculated according to the same scarcity principle. Marginalist economics is thus about choice, the allocative functioning of markets, the de-centralisation of decisions, and is therefore compatible with a liberal world view, and even of a democracy where the electorate picks representatives to relay their interests into public policy.

The dominant figure in economics in the last thirty years leading up to 1914 was Alfred Marshall. His book, Principles of Economics, was an instant success. “Rarely in modern times, the Scotsman wrote, has a man achieved such a high reputation as an authority on such a slender basis of published work”. [41] Keynes records the reasons for the many delays before publication, including his own high standards: “..the more I studied economic science, the smaller appeared the knowledge which I had of it, in proportion to the knowledge which I needed”, he wrote. Keynes judgement is that “ as a scientist he was, within his own field, the greatest in the world for a hundred years” [42]… “he was conspicuously historian and mathematician, a dealer in the particular and the general, the temporal and the particular, at the same time”.[43] Marshall realized that his discipline required a profound knowledge of the actual facts of industry and trade. So he frequented business people and trade unionists. He deployed mathematical and diagrammatic tools to illustrate theory, contributed to the work of royal commissions, and made original contributions-according to Keynes- on the quantity theory of money; the distinction between the “real” rate of interest and the “money” rate of interest; the enunciation of the concept of “purchasing power parity”; methods of indexing numbers; as well as the concept of consumer or producer surplus; or the idea of the short, medium and longer term in the adjustment of supply to demand over time. Economics, he considered, was a voyage of discovery, not a set of universal dogmas. Not least, he was well aware that a chief fault in “English economists at the beginning of the century, was that they regarded man as a constant”and gave themselves little trouble to study their variations”. [44] On governments, he considered they should provide statistical support for the benefit of business, but not enter the field of production of goods and services. His influence was immense: by 1888, half the economic chairs in the UK were occupied by his pupils.

Concluding remarks

Utilitarian economics thus spawned a huge and clamorous field of studies, ranging from free market economics, to revolutionary socialism, class war and competition understood as the survival of the fittest. One distinction that can be made over the two hundred years is between Smith, Malthus, Ricardo and J.S. Mill who debated, and Bentham, Mills senior, Marx and Engels who asserted. A consistent problem that they all had to deal with was defining the subject they studied: did it embrace all of human experience, or could it be reduced to building models on a couple of axioms or of stylized facts? The problem was highlighted by Macaulay’s attack on James Mill, to wit that human affairs were not reducible to simplistic axioms, and had to be studied in a context of history, with all the diversity entailed thereby. It ended fortunately in the tranquil study of Alfred Marshall, who-following the marginalists- pushed ahead to par the study of economics down to its barest essentials, but always remained highly alert to the limits of the discipline he was forging, and the need not to consider that what followed from the logic of the model might not follow at all from policy applied to any specific human reality. His crucial insight was that the study of markets was an exploration, a discovery, a permanent questioning. He proposed a plethora of tools, all of which have endured, and may be considered as one of the main founders, if not the main founder of the modern school of economics. That school soon ditched his humility, as it hitched itself to power, money, and the business of war. We turn now to the fourth rider of the European apocalypse- the phenomenon of nationalism.

[1] Boris Mirkine-Guetzévitch, La pensée politique et constitutionnelle de Montesquieu, Paris, Receuil Sirey, 1952, p. 14

[2] Jonathan Israel, “Scottish Enlightenment and Man’s “Progress”, in Democratic Enlightenment: Philosophy, Revolution and Human Rights 1750-1790. Oxford University Press, 2011. p. 233

[3] De l’Esprit, II, 5 ; Œuvres, Paris, 1795, Vol I, p.208.

[4] De l’Esprit, II, 24 ; Vol.I, pp.394 ff.

[5] The Wealth of Nations, New York, Modern Library, 1937, p.651.

[6] https://www.institutcoppet.org/turgot-discours-sur-les-progres-successifs-de-

esprit-humain-1750/

[7] « Jeremy Bentham and the British intellectual response to the French Revolution », Journal of Bentham Studies, London, UCL Press, (Electronic) 01, January, 2011.

[8] The People’s Charter with the address to the Radical Reformers of Great Britain and Ireland and a Brief Sketch of its Origin, London, C.H.Elt, 1848.

[9] Victorian Years : 1841-1895, Halévy’s History of the English People in the Nineteenth Century, Vol.4. London, Ernest Benn, 1952. pp. 113, 132.

[10] Ibid. p. 304.

[11] Letter from Adam Smith, LL.D. To William Strahan Esq. Kirkaldy, Fifeshire. Nov.6 1776. from: Early Biographies of David Hume, ed. James Fieser (Internet Release, 1995.

[12] The Life of David Hume : Written by Himself, London, W.Strahan and T.Cadell, in the Strand, 1777.p. xxxvi.

[13] John Maynard Keynes, “The First Cambridge Economist”, Essays in Biography, London, MacMillan, 1933, pp. 95-150.

[14] John Stuart Mill, Chapter Two, Moral Influences in Early Youth. My Father’s Character and Opinions, Autobiography, EBook, updated 2021. https://www.laits.utexas.edu/poltheory/mill/auto/auto.c02.html

[15] Thomas Huxley, « Agnosticism and Christianity » pp.96-119, in Christianity and Agnosticism: A Controversy, New York, The Humboldt Publishing Company, 1989.,p.97.

[16] James Murphy, « Religion, the State and Education in England”, History of Education Quarterly, Spring 1968, Vol.8, No 1, Spring 1968, p. 34.

[17] Cited by James Murphy, ibid. p. 49 , from Hansard Parliamentary debates, 3rd ser, CLXXVIII, col.1,549.

[18] Cited By David Tribe in “100 Years of Freethought” by David H. Tribe (, London, Eml, 1967.

[19] Quoted from The Wealth of Nations, by Giancarlo de Vivo, “Adam Smith and his Books”, Contributions to Political Economy, 2001, 20. Pp.87-97.

[20] « Touching Oxford : a Letter to Professor Nebel”, Blackwood’s Edinburgh Magazine, 79, February 1856.pp. 179-83.

[21] Victorian Years : 1841-1895. Halévy’s History of the English People in the Nineteenth Century, Vol.4. Ernest Benn, 1948.

[22] Will and Ariel Durant, The Age of Voltaire, New York, Simon and Schuster, 1965, p.125.

[23] Quoted in The Natural History of Religion, in Dialogues and Natural History of Religion, edited by J.A.C. Gaskin, Oxford and new York, Oxford University Press, 1993, p.185.

[24] Lisa Smyth, The hidden theology of Adam Smith, European Journal of Economic Thought, 8: 1 Spring 2001, pp.1-29.

[25] William Ewart Gladstone, , A Corrected Report of the speech of the Right Hon. W.E.Gladstone M.P. , at Greenwich , October 28, 1871, London, John Murray, 1871. Pp.30-31. The speech was also delivered on 28 October 1871 at Blackheath.

[26] A.J.P. Taylor, English History 1914-1945, Oxford University Press, 1965.p.1.

[27] G. Koolman,, « Say’s Conception of the Role of the Entrepreneur » Economica, Vol. 38, Issue 151, 1971, pp. 269-286.

[28] Le Nouveau Christianisme, Dialogues entre un conservateur et un novateur, Bossange Père, 1825.

[29] This is no doubt a controversial interpretation of a controversial article, where commentators are at odds about whether or not Marx here is being anti-semitic, or is developing his ideas about the relation between formal “religion”, and his still developing ideas about materialism. A modern article on this subject is Paul Johnson, Marxism v. The Jews, Commentary, April 1984. Available on the internet.

[30] Lettres inédites de John Stuart Mill à Auguste Comte, Paris, L.Lévy-Bruhl, 1899, quoted in Victorian Years : 1841-1895. p.399.

[31] Kathleen Blake, Pleasures of Benthamism : Victorian Literature, Utility, Political Economy, Oxford University Press, 2008, p.7.

[32] Adam Smith, The Wealth of Nations, London, Everyman’s Library, 1970.Volume I. p.10.

[33] Ibid p.13

[34] Ibid p.400.

[35] Volume Two. p.180.

[36] Jacob Viner, “Adam Smith and Laissez-faire,” The Journal of Political Economy, Volume 35, No.2, April 1927. pp.198-232.

[37] Thomas Malthus, An Essay on the Principle of Population, London, Baltimore, Penguin Books, 1970. pp.76-77.

[38] Derek P. H. Allen, « The Utilitarianism of Marx and Engels”, American Philosophical Quarterly, Volume 10, No. 5. July 1973.pp.189-199.

[39] Quoted in Valentino Gerratana, Marx and Darwin, New Left Review, Issue 82. November-December 1973. Pp.60-82.

[40] Quoted in Valentina Gerratana, Marx and Darwin, p.74.

[41] Quoted in John Maynard Keynes, “Alred Marshall”, Essays in Biography, London, MacMillan, 1933, pp. 150-266.

[42] Ibid. p. 169.

[43] Ibid p.171.

[44] Ibid p.209.