The Year of Covid: Political Religion and the Cultural Wars: The First World war: Origins, Course, Impact.

This is the eleventh essay in my series on cultural wars: its subject is the first world war. In the last chapter, I concluded that the principle reason for the outbreak of war was the muddle headedness of the small company of leaders of Germany, Austria-Hungary and Russia, rather than some abstract force such as nationalism, the competition between states in markets, or the competing coalitions of the Central Powers and the Entente. What mattered though is that the leaders of these powers proved unable to think coherently in the political constellation of the time. They wanted a short and localized war, but they got a general European war. The French were consistent in seeking to build a coalition against Germany, and to reverse the results of the 1870 war. Sir Edward Grey was also consistent in seeking to deploy the Council of Europe mechanism to the solution of the Balkans problems, and British foreign policy was consistent in resisting any power seeking to establish hegemony in Europe. But he failed on both counts, and war was for him and his government the undesired but ineluctable result. In this chapter, we trace the course of the war; the record of losses, particularly during the early months; the voices calling for peace and the factors contributing to the war’s continuation; and last but not least, the peace treaties, and the initial debate about who the guilty men were who launched the war.

The course of the war

Once mobilization of the armed forces of Europe was set in train, the political leaders sensed control draining into the hands of the generals. Austria-Hungary held Serbia responsible for the assassination of Franz-Ferdinand, the heir apparent, and declared war on Serbia on July 28, Russia came to Serbia’s defence, and mobilized on July 30, from fear of being caught flat-footed by Germany. Two days later, Germany declared war on Russia. On August 2, Germany occupied Luxembourg, and the next day declared war on France while demanding free passage of their troops through Belgium. This was refused. Sir Edward Grey, the British Foreign Secretary, speaking in the House of Commons warned Germany against making a lunge for European hegemony by invading Belgium. But on the early morning of 4 August, Germany invaded; the King of Belgium, Albert I, called for assistance under the 1839 Treaty of London; Grey sent Berlin an ultimatum to withdraw by midnight; when that failed, Germany and Great Britain were at war. Britain’s entry ensured that what had begun as a local conflict in the Balkans flared into a Europe-wide conflict. The Ottoman Empire joined the conflict in November.

At the outbreak of the war, the German intent was to crush France first, then turn on Russia. This plan-the Schlieffen Plan-failed, and by the end of 1914, the Western front stretched along a continuous line of trenches from Switzerland to the English Channel. On the Eastern front, the Germans won a crushing victory at the battle of Tannenberg between August 23 to August 30, ending in the near total destruction of the Russian Second Army and the decimation of the First Army. Russia survived, but war extended to the south as Bulgaria, Italy, Romania and Greece joined in the course of 1915, and the western allies, France and Britain, sought to take the Ottoman Empire out of the war through the landings at Gallipoli. The Gallipoli battle lasted from February 1915 to January 1916. That year,1916, was the year of major battles, Verdun, the Somme, the Brusilov offensive and the sea battle of Jutland. In early 1917, the United States entered the war on the side of the allies, and the Bolsheviks seized power in October, as the Russian armed forces disintegrated. A Bolshevik ruled Russia made peace with Germany in early 1918. Bringing its troops westwards, Germany then launched what its leaders hoped would be a knock-out blow in March 1918. But in spite of early success, the offensive ran into increasingly stiff opposition. A successful allied counter-attack shook German confidence in success. By the end of that year, Bulgaria, Austria-Hungary and the Ottoman Empire were suing for peace. This left Germany isolated, its army on the verge of mutiny, and the government facing revolution at home. On 9 November, the Kaiser abdicated, and the armistice was declared on 11 November 1918. The Russian, Ottoman and Austria-Hungary empires dissolved, with far-reaching consequences for Europe, the Middle East and the wider world. The ensuing Paris Peace Conference (1919-1929) involved a number of crucial decisions, including the creation of a League of Nations, five peace treaties with the defeated states, the creation of newly independent states, and the transition of German and Ottoman possessions as mandated territories to Britain and France.

Let us cover the four years of the war in slightly more detail. Within the first few months of the war’s outbreak in August, the Austrian-Hungarian armies attempted three invasions of Serbia, none of which ended in success. The initial military action of the First World War took place around the Cer Mountain between Austria-Hungary and the Serbs. Clashes between the two armies escalated into full-scale battle, lasting from August 12 to August 24, ending in a collapse of the Austrian army with many drowning in the Drina river as they fled in panic. A second invasion was launched at the battle of the Drina, when the Austrian-Hungarians had to retreat in order to avoid encirclement. A third offensive was opened in late October, this time reaching into northern Serbia and the capture of Belgrade, but at the battle of Kolubara, a Serbian counter-offensive drove the Austrians out of their territory, before the end of December. Serbia’s defeats of the Austria-Hungarian invasions of 1914 have been counted among the major upset victories of the last century. [1]

They were not alone that year. The objective of Aufmarsch II West, as the Schlieffen Plan was officially titled, was to crush France before turning the weight of German armed forces against Russia. The Plan prescribed a sweep through Belgium, then a swing south, the encirclement of Paris and the trapping of the French Army against the Swiss frontier. Four fifths of Germany’s available military resources were allocated to the task. Initially, they were very successful; the small 100,000 man British Expeditionary Force (BEF) was driven into full retreat. The French offensive into Alsace-Lorraine proved a costly failure in what became known as the Battle of the Frontiers. But as the German armies closed in on Paris, a gap opened up between them, into which the French army marched, backed by the BEF. The German army fell back up to 40 to 80 kilometres. This battle of the Marne was one of those rare battles, which changed the course of history. As Hew Strachan writes, “The Marne was a decisive battle, and its consequences were strategic”. [2] Exhausted, both armies settled into trenches; the German troops dug into strong defensive positions on French territory and stayed there for four long years. But they had failed to achieve a decisive victory, the primary objective of which had been to avoid a two front war. Crown Prince Wilhelm told an American reporter “We have lost the war. It will go on for a long time but lost it is already”.[3]

Meanwhile, two Russian armies had entered East Prussia on August 17, as agreed on previously with France. The two armies moved in to Galicia, and forced Germany to divert troops away from the western front. But they had done so poorly prepared, and as it turned out, poorly led. Their railway equipment could not be deployed on German lines, so that their armies had to advance on foot, while the Germans could easily decipher their communications. The combatant armies moved into contact on August 23, when German command was handed over to Field Marshall Paul von Hindenburg, supported by his staff officer, Erich von Ludendorff. The two turned out to be a formidable duo. They decided to annihilate the first army, while moving to encircle the second. By August 31, victory was confirmed with the Russians recording enormous losses in terms of killed, wounded and lost matériel. This battle of Tannenburg, as it came to be dubbed, was followed a week later by the battle of the Masurian lakes, leading to the Russian forces falling back into Russian territory in order to avoid encirclement. What these two confrontations revealed was serious weaknesses in the Russian forces, and the superior skills of the German army. They also bolstered German morale, confirmed the reputations of Hindenburg and Ludendorff as effective wartime leaders, and in effect began the Kaiser’s demotion to be no more than the nominal supreme commander of Germany’s armed forces.

Six months into the war presented a sobering record for all combatants The war was promising neither to be short, nor local, nor cheap. Turkey had joined in the side of the Central Powers in the winter of 1914. In early 1915, Italy joined on the allied side. German troops, though, occupied French territory, and deprived France of its main industrial centres. The war had flared out globally, with allied forces seizing all German territories in the Pacific; German forces resisted more effectively in Africa, holding out until two weeks after the end of the fighting in Europe in November 1918; the Indian Congress movement backed the war, with the expectation of independence as a reward, a commitment to which the British government pledged in 1917. The British Indian army, all volunteers, numbered 1.5 million and served in all theatres.[4]

Most importantly however were the human losses . On the eastern front, Russian losses of killed, captured and prisoners, were colossal, and inaccurately recorded. At the battle of Tannenberg, by 31 August, the Germans had taken 92,000 prisoners, and 50, 000[5] to 78,000[6] dead or wounded. Within the first nine months, the Russians lost 2 million men, 764,000 of them as prisoners. [7]Enver Pasha, the Turkish general, took 90,000 men in an attack on Russia in the Caucasus, and in December of 1914 lost 88% of his force at the battle of Sarikamish[8]. On the western front, French casualties exceeded 260,000 including 75,000 killed by the end of August. On the 22nd August alone, France lost 27,000 killed. By September 6, the German army had lost 265,000 killed, wounded or missing,[9] and by the end of the year the figures of German troops lost reached 800,000, 116,000 of which had been killed. [10] The British Expeditionary Force initially deployed about five divisions, or 100,000 men; they were involved in two fierce battles, the battle of the Marne, and First Ypres; by the end of November, casualties numbered 89, 964; [11] as the British official history recorded, the old British army which crossed to France in August, had ‘gone beyond recall’. Finally, on the southern front, in the clash between the Austria-Hungarian armies and Serbia, Austria-Hungary by December had suffered a million casualties, including 189,000 dead fighting the Russians; and Serbia had lost 163, 557 men out of a population of 5 million, including 69,022 dead.[12] By 1918, Serbia had lost one quarter of its population, the highest ratio of casualties to population in the entire conflict.[13]

In the following year of 1915, the powers went through similar developments. Proposals for a peace, of which there were one or two, were rejected. The hard men moved to prominence in all the contestants: the first country to centralise production was Germany in 1914 under the direction of Walther von Rathenau, head of AEG, the electrical giant; Lloyd George became Minister of Munitions the coming year following the scandal over the lack of shells in the Gallipoli campaign; Albert Thomas, a socialist, created what became the Ministry of Munitions. These measures helped to cartellise the national economies more than they already were. The major military leaders of the war were all in their saddles by the end of the year at the latest: Alexander Haig became Commander-in-Chief British forces in France; Josef Joffre in France; Hindenburg in Germany. On Russian demand, Great Britain and France launched a diversionary action against the Turks on the Gallipoli peninsula, a confrontation lasting from February to1915 to January 1916. The Turks lost 300,000 killed, wounded and missing; [14] of which an estimated 86,692 were killed, the British lost 40,000, the French 19,000, the Australians 8,709 and the New Zealanders, 2, 721.[15] Italy joined the western powers in May, and fought four battles on the Isonzo that year, suffering 235,000 casualties, of which 54,000 were killed. Both Gallipoli and the entry of Italy had longer term results: these battles all hastened the development of a national identity in Turkey, Italy, Australia and New Zealand. In Italy, both liberals and a section of the socialist party under Benito Mussolini pushed for intervention in the war, accelerating thereby the radicalization of Italian politics. A further innovation was the use of poison gas, first by the German army at the second battle of Ypres in April 1915, and then by the British at the battle of Loos in September. This turned out to be a disaster, as the gas blew back into the faces of the advancing British troops. The use of gas had been outlawed by the Hague convention of 1899, and represented a general trend to explore the ever-expanding frontiers of violence.

In December 1915, the allies-Russia, France, Great Britain and Italy- committed to simultaneous attacks against the Central Powers. The battle of Verdun opened in February 1916, and ground to closure in December. General Falkenhayn’s idea was to bleed the French army to death. The bleeding however was reciprocal: Hew Strachan records German losses as 337,000, of whom 143,000 were killed; French casualties totaled 377,231, of whom 162,440 were killed. [16] At Easter time, a few thousand Irish nationalists staged an uprising in Dublin, for which they received German support. The nationalists tried to raise volunteers to their cause among Irish prisoners of war. They had no luck, and 140,000 Irish volunteers in the British armies continued to serve loyally, of which 27 to 35,000 were killed. The sea battle of Jutland occurred on May 31 to June 1, engaging 100,000 men in 250 ships, where the Germans lost 11 ships and the British lost 14, leaving Royal Naval supremacy unimpaired on the seas. The battle of the Somme opened on July 1, the bloodiest single day of British military history, recording 57,500 casualties of which 19,200 were killed. The Somme offensive led to an estimated 420,000 British casualties, along with just under 200,000 French[17]and 500,000 German casualties. [18] The Brusilov offensive opened on the eastern front in July, in which the Russians took 400,000 prisoners, inflicted losses totaling 600,000, and the Russians lost 1 million men, killed, wounded, captured or lost. [19]

There seemed no end to the misery. War had long been joined and the losses demanded justification through victory. Germany took the fatal decision to wage unrestricted submarine warfare, which was immediately followed by the newly elected president, Woodrow Wilson, deciding to break off relations. The three major battles of the year were the battle of the Aisne in April, the Third Battle of Ypres, remembered in the United Kingdom as the battle of Passchaendale in July to November, and the battle of Caporetto of October. At the first battle British casualties amounted to 160,000 men;[20] German were 163,000; and French losses amounted to 187,000, [21]prompting French troops to mutiny. Discipline was restored ruthlessly, but their offensive spirit did not return. At Passchaendale, British casualties amounted to 275,000 of which 70,000 were killed; A.J.P. Taylor puts the German losses at near 200,000. [22] The battle, Taylor observes, “was the blindest slaughter of a blind war”. [23] On the southern front, the Central Powers recorded a victory at Caporetto, when the Italian army collapsed, falling back 70 kilometres to the river Piave. There were mutterings about the purpose of it all in the British army, and across Europe, a rash of peace feelers, which were as promptly squashed by the hard men in the driving seats of the major protagonists. Ludendorff, Lloyd George, Haig, and General Nivelle in France all believed that a knock-out blow was possible. In November, Georges Clemenceau became Prime Minister in France, and announced to the national Assembly that “You ask me for my policy. It is to wage war. Home policy? I wage war. Foreign policy. I wage war. All the time in every sphere, I wage war”. Lloyd George called for a co-ordinated strategy- the first stirrings of what after 1945 burgeoned into the European integration strategy. At the time, there was no political space for peace.

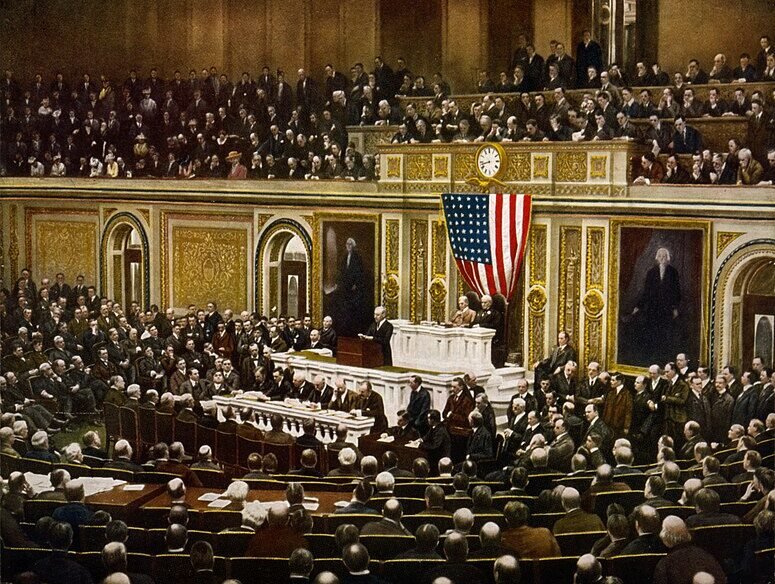

The year 1917 was the year when the old Europe-centred world ended. Yearnings for peace turned in Russia to revolution. The Tsar resigned in March, Lenin arrived the next month in Petrograd, Russian soldiers began to desert, and the revolution was under way. In April, the U.S. Congress declared war on Germany. Another major development with long term implications was the British government’s announcement in November for Palestine to become a national home for the Jews. That month, Lenin seized absolute power in Russia, and in December, signed an armistice with the Central Powers, thus liberating large numbers of German troops for redeployment westwards. In January, Wilson delivered a speech to the US Congress,, spelling out his famous 14 points on which a possible peace could be established: as Clemenceau commented, “The Lord was satisfied with ten”. They included: open diplomacy without secret treaties; free trade; a decrease in armaments; an adjustment of colonial claims, and an evacuation of all Central Powers from Russia. The point with the most immediate impact on multi-national Austria-Hungary was the right of nations to self-determination.

It was becoming clear that, with fresh American troops pouring in, the decisive battle would be fought on the western front. To ensure that Russia was well and truly knocked out of the war, and in order to create its own sphere of influence in Mitteleuropa, Germany imposed crushing terms on revolutionary Russia at the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk in early March: the Ukraine, Poland, Belarus, the Baltics and Finland achieved independence as did the Caucasus; Russia lost a third of its population, most of its industry and the rich farmland of the Ukraine. A couple of weeks later, Ludendorff launched Operation Michael for an offensive on the western front. The offensive was greeted with initial triumphs, but by July, the French struck with mass tank attacks, and the German armies broke; on August 8 the British attacked, on what Ludendorff called “the black day of the German army”, shattering German faith in ultimate victory. The Americans, soon to number 4 million men, attacked late September at Argonne, and three days later, Ludendorff insisted that Germany had to reach an immediate armistice. Allied troops that October made significant advances; declarations of independence were made by the representatives of Hungary, the Czecks, and Croatia; the Turks sued for an amnesty; followed by Austria-Hungary, the abdications of the German Kaiser and Emperor Karl; the proclamation of the German republic, and the demand by German Austrians to join the new German state. The war’s end is celebrated at the eleventh hour of the eleventh month of the year 1918.

Why did the belligerents keep fighting?

Of the 60 million soldiers who fought in the First World War, the armies of the Central Powers mobilized 25 million soldiers of whom 3.5 million were killed; the Entente Powers deployed 40 million soldiers, and lost more than 5 million killed. The worst hit of the larger contestants relative to population was France, which lost nearly 2 million killed, depleting the younger generations in particular. They left behind them 680,000 widows. Another 600,000 died from French Africa.[24]Serbia lost the most per head of population among the smaller belligerants. Russia lost an estimated 1,811,000 killed and a further 1,500,000 civilian deaths. The Hapsburg Empire lost 1.5 million ; the British Empire 1 million, while the bodies of 500,000 were never found; Italy lost 460,000. The number of Turkish lives lost remains unknown. Over the whole war, these deaths sum at a rate of 6,000 per day. The death rate of the first six months was higher still, worse even than 1916, and the huge battles at Verdun, the Somme, and the Brusilov offensive, not to forget the war’s only major sea battle at Jutland in the North Sea. Then there are the near 7 million civilians, who died from starvation, including the Ottoman massacres of the Armenians. This brings the total of deaths in the war to around 16 million people.

Why did the combatants persist in their military efforts in the light of the losses they endured? The death of Franz Ferdinand and Sophie, the invasion of Belgium, the recuperation of Alsace-Lorraine or German fears of encirclement by hostile powers may all have seemed real enough, demanding of action. But in retrospect the question hovers whether the consequences which flowed from this catastrophe were worth the sacrifice. In his account of the First World War, John Keegan concludes that the war remains a mystery, and that no clear response is possible. This is a comment about how the First World War is seen by those who live many decades after, but it was definitely not the way that the people who lived through it. [25] To them, it was less a mystery than a pressing reality. The temptation for us who live now is to think retrospectively, rather than to enter into the past, and remember that the people of the time did not know the future, even though many of them sought to divine what could happen. All we can do is to enter into the thoughts, as far as that is possible, of those who left records of what went through their minds at the time. We have to make a leap of imagination.

Once, the participant nations had joined battle , the doors of war closed firmly behind them. Exit grew increasingly difficult in multiple ways. Both the Entente and the Central Powers took positions which greatly reduced their discretionary powers to make decisions on the hoof for themselves in their own best interests. The narrowing of discretionary powers had begun even before war was joined, when Berlin gave Vienna its”blank cheque” to go ahead and punish Serbia. Berlin thereby handed the initiative to Franz Josef’s government, which opted for delay, prevarication and finally for war-a decision which brought Russia into support of Serbia. One month into the war, the Entente powers issued a declaration undertaking not to conclude a separate peace and only to demand terms of peace agreed among the three parties. A week later, Chancellor Bethmann-Hollweg, addressing primarily a domestic audience, drew up a programme of objectives, which included permanent control of Belgium, of North East France and Central Africa. To this was added the idea of Mitteleuropa, developed in a best selling book published in 1915 by Friedrich Neumann, Mitteleuropa, which proposed that the states and peoples included adopt German associational methods as their standard.[26] The implication for the Hapsburg Monarchy of course was one of subservience in a Berlin-centred geographic space.

Evidently, the concept of Mitteleuropa was scarcely compatible with free trade which stood as one of the pillars of Wilson’s Fourteen Points. This was not the only difference, but it played into the diplomacy of European reactions to the entry of the United States to the war. The presence of a third party, which aimed to join the battle but also operate as a mediator between the belligerents, made their responses that much more complex. Berlin answered first to Wilson’s requests for terms, while the allies then submitted their list which in effect amounted to demanding autonomy for all central European states, and for the disintegration of the Hapsburg monarchy. Under these circumstances, with trust at a discount between both Central and Entente powers, let alone across the divide, Wilson’s initial peace proposals faltered, leaving the outcome of the war to be decided by force of arms.

As soon as war was joined, it was evident that the leaders in all participating countries were overwhelmed by the results of applying the new technologies of war, particularly the heavy artillery, machine guns, quick firing rifles, trench mortars, high explosives, grenades, flamethrowers, not to mention poison gas. Take for instance the curious case of the red trousers that French infantry continued to wear in the early months of the war: a French Minister of War in 1911 had correctly predicted that “this blind stupid attachment to the most visible of colours will have cruel consequences”. But his replacement declared that “Red trousers are France”, on grounds of not challenging the army’s morale, and he refused as a consequence to abolish them, with the result that French soldiers died in vain attacks as easy targets for their grey-clad foes. August 22 1914 went down as the worst day in the annals of French military history, when 27,000 were killed, comparable to July 1, 1916, the bloodiest single day in the history of the British army, which suffered 57, 500 casualties, including 19,200 dead. As John Keegan, has written, “the simple truth of 1914-18 trench warfare is that the massing of large numbers of soldiers unprotected by anything but cloth uniforms, however they were trained, however equipped, against large masses of soldiers, protected by earthworks and barbed wire and provided with rapid-fire weapons, was bound to result in very heavy casualties among the attackers”. [27]

The generals of all sides found the means elusive of learning how to operate at lower cost in casualties. One answer was to praise the virtues of true grit: as Keegan points out the watchword for Germans became Durchhalten, in modern colloquial speech, “Hang on in there”. This of course did not relieve the blood-letting, nor did it calm the nerves of soldiers facing the prospects of battle in Verdun, the Somme, the Brusilov offensive or the battle of Passchendaele. A more creative strategy was to escalate the use of terror: the first time that chemical weapons was deployed was in April-May 1915 by the Germans at the second battle of Ypres; the British were quick to follow suit. More lethal versions were then deployed by the Germans in the form of “mustard gas” in July 1917, with most of the 186,000 British chemical weapon casualties coming from this variant. Tanks served the same purpose-to drive enemy troops out of entrenched positions, but had to contend with mud and technical hitches. Collateral damage to the war took various forms such as the mass killings of Armenians by the Turks, epidemics of typhus, and the so-called Spanish flu which spread around the world as of early 1918. All sides sought to undermine the loyalty of the other’s imperial subjects: Germany hoped, but failed, to spark jihad against the British Empire, but the allies succeeded eventually in undermining the loyalty of the nationalities of the Hapsburg Empire. Both British and French co-operated in stimulating Arab nationalism against the Ottomans.

Nationalism played its part. The Irish and Welsh backed Lloyd George’s championing of the cause of small nations-the reason he gave for switching sides to the pro-war faction in Asquith government. Great Britain went to war in support of international law, and also in opposition to the hegemony of any one power over the rest of Europe. The French government mobilized the language of the French revolution, and had Joan of Arc enthroned as the icon of “l’union sacrée”. For Belgium as for France, the purpose of the war was to secure basic freedoms, assert control over their territory and, for France, to achieve the return of the lost territory in Alsace and Lorraine. Italy joined the allies for clearly identifiable nationalist reasons in 1915. For Germany, the war was fought in the name of defending Europe against Russian “barbarism”, and in October 1914, four thousand German academics signed a manifesto identifying German culture with Prussia’s military essence. As Keegan writes, the peoples of Europe fought the First World War because they believed in- or at least accepted- the causes for which their nations stood. It was emphatically not a war without purpose”. [28]

But one should not under-estimate the skepticism of the troops enduring the privations of the trenches, the bombardments, and the terror of rushing into a hail of bullets. They were often-times torn between loyalty to their colours and a slaughter, which was forever fostering the question of whether it was blind and with no recognizable purpose. Discipline occasionally broke, especially in the French army, and in the latter months of the war. Troops died, or lived as individuals, and it was the same for the generals and leaders. Individual statesmen or generals had permanently to be aware of their own position: General Falkenhayn, Chief of the German General Staff, proposed in November 1914 that Germany should seek a separate peace with Russia; his ideas were poorly received; and he went on at Verdun to propose the German strategy of bleeding the French army white; yet he was attacked by the faction supporting Field Marshall von Hindenburg, on the grounds that Germany was not in a position to win a decisive battle, and should therefore negotiate. The hard men who advocated for the final knock-out blow tended to win in the struggles for power at the top of the armed forces: Joffre, Nivelle, Hindenburg, Ludendorff and Haig, and finally on the civilian side George Clemenceau and the extra-ordinarily sinuous David Lloyd George. Those who advocated peace placed their influence on the line, and, unless they retracted fast, lost. Lloyd George may be said to have been all things to all men, but to have remained his own man. A living demonstration that it is possible to be a genius politician.

The legacy of the war was as devastating as its course. John Keegan summarises it thus: “The legacy of the war’s political outcome scarcely bears contemplation: Europe ruined as a centre of world civilization, Christian kingdoms transformed through defeat into godless tyrannies, Bolshevik or Nazi, the superficial difference between their ideologies counting not at all in their cruelty to common and decent folk. All that was worst in the century which the First World War had opened, the deliberate starvation of peasant enemies of the people by provinces, the extermination of racial outcasts, the persecution of ideology’s intellectual and cultural hate-objects, the massacre of ethnic minorities, the extinction of small national sovereignties, the destruction of parliaments and the elevation of commissars, gauleiters and warlords to power over voiceless millions, had its origins in the chaos it left behind.”[29] The crazed ideologies of race and class feeding into a widespread nationalism preceded the war, but its course and outcome gave them free rein in subsequent years.

Peace initiatives.

The peoples of Europe were still largely Christian in ethos, if not in belief. The hammer blows to the old Christianity of the medieval papacy had come with the Protestant movements, and these still played out during the World War of 1914-18, in that the Papacy appreciated that the prime Catholic monarchy of Europe was the Hapsburg Empire, and was very much aware that Prussia was Protestant, the United Kingdom was Anglican in England, Catholic in southern Ireland, and Calvinist in Scotland and northern Ireland. Relations between the Vatican and the liberal states of the Third Republic, of Rome, Madrid, and since 1910, of Portugal were marred by liberalism’s anti-clericalism, which was matched by the papacy’s hostility to everything that reeked of “modernism”-whereby was meant at the time, as now, that the Church should adapt to the world, rather than that the world should heed the Christian message. Definitely, the causes for which the war was fought were highly secular, having much to do with territory, nationality, security, international law, and with a strong component of Darwinism, whereby it was considered to be the destiny of the peoples of Europe to be pledged to a fight for survival. The exigencies of war requiring absolute dedication to the common task of victory was the mood in all belligerent states. It was this aspect of the war that ensured the war would be fought to the finish, and that the varied peace factions of the belligerent countries confronted hurdles to their objections to war that proved insurmountable: their opponents harangued them as apatriotic; their pacifism was a gift to the enemy; it was not the classes that were antagonistic, but the peoples; nations were races, bound to struggle for life and living space. Secularist arguments for peace thus died almost the moment that they were uttered. The First World War was pre-eminently a secularist war.

One by one the secularist progressive forces of Europe succumbed to the drumbeat of national unity. The German Social Democrats were the largest, and best organized socialist political force in Europe. They had been at the forefront of the cause for peace, yet they were persuaded by Bethmann-Hollweg to vote for the war in August 1914 on the grounds that the enemy was reactionary Russia; Keir Hardie, the founder of the Labour party, died, it is reported, from a broken heart at the sight of the workers of the world going to war against each other. Jean Jaurés, the French socialist party leader and friend of Keir Hardie, was assassinated for his efforts. Jaures had planted his standard on the ground of a patriotic socialism in his book, L’Armée nouvelle, in which he critiqued Marx’s phrase that “proletarians have no fatherland”. Wars, he contended were caused by the clash of capitalist interests, and it was the duty of the working classes to oppose them.[30] Two years later, he had opposed the law extending national service to three years, and over the course of 1914 had sought to promote understanding between France and Germany- a particularly arduous task in view of the fact that many of his compatriots agreed that the country should seek revenge for the defeat of 1870 and the loss of Alsace-Lorraine. He was also opposed to the alliance with Russia, and was active in trying to organize a co-ordinated general strike against war in both Germany, France and the United Kingdom. But on July 31, as war pressed ever closer, he was assassinated just before 10 pm at the Café du Croissant on the Rue Montmartre in Paris. His death was then celebrated by President Poincaré as contributing to the union sacrée– to which the socialist party colleagues now subscribed but that had hardly been at the heart of Jaurés’ campaign for peace. He died for his commitment against war, killed by a 29 year old French nationalist. In the longer term, European social democracy came to identify nationalism as the cause for war; in the immediacy of 1914, the majority of social democrats signed on for the war.

Opposition, ineffective as it turned out to be, came from the old seats of what Europe’s progressive forces would dub European reaction: the Vatican, Lord Lansdowne, the Catholic Zentrum party in Germany, and the Hapsburg Monarchy in the form of the Emperor Karl. The old Pope, Pius X, died on August 20, 1914, after the war’s outbreak and just before the first great clashes were about to occur. On September 3, the College of Cardinals chose Giacomo Battista della Chiesa as Pope Benedict XV. The new pope had a long experience in the papal diplomatic service, but took over at a time that historians consider to be a nadir in papal influence.[31] The Vatican maintained diplomatic relations with only a clutch of states, notably Prussia, Russia, the surviving Catholic monarchy of Austria-Hungary, and Belgium, as well as with a few Latin American states, but neither with France nor Great Britain. Benedict rustled together a small coalition of secondary powers, such as Spain, and Switzerland, eventually extending to the United States, but had to broach his peace initiatives in such a way as to avoid ruffling the feathers of patriotic French, German or Italian Catholics, who supported their respective hostile national positions; the anti-Catholic prejudices of William II or Woodrow Wilson; and the vehemently anti-clerical Clemenceau. The contending powers had little intent to reach a peace, but were keen to be associated with the papacy’s moral prestige. In retrospect, that prestige was rooted in Benedict’s single minded pursuit of peace: peace among nations; peace among classes; peace among religions, and within them. When he ascended the throne of St Peter, the Vatican had 14 nuncios; when he died unexpectedly at the age of 67 in 1922, there were 27. Two years before his death, the Turks had erected a statue to him in Istanbul to commemorate the “great pope of the world tragedy…the benefactor of all people, irrespective of nationality and religion”. [32]

His biographer has written that throughout the first world war, the Vatican was “an impotent bystander”.[33] But Benedict was not to be discouraged. It was the war that provided the main focus for the new Pope’s pontificate. He published his first encyclical, Ad Beatissimi Apostolorum in November 1914, when it was already becoming evident that the war was heading for prolonged stalemate. [34]The war, the encyclical stated, is “the suicide of civilized Europe”. It is being waged because the belligerents have divorced themselves “from the holy religion of Christ”. “The combatants are the greatest and wealthiest nations of the earth: what wonder then, if, well provided with the most awful weapons modern military science has devised, they strive to destroy one another with refinements of horror”. There were, he suggested, other ways of rectifying violated rights than war. In July 1915, Benedict then published an apostolic exhortation, “To the Peoples Now at War and to their Rulers”. The exhortation was timed to coincide with Italy’s entry to the war, to which the Vatican was opposed. His biographer writes that this document meant a change to active diplomacy that culminated two years later in his peace note of August 1917. [35] He presented the seven-point peace plan in August 1917, when there were already plenty of signs that violent revolutions were brewing: the Tsar had abdicated; discontent in the French army was rife; food shortages afflicted the Hapsburg empire; the United States had entered the war. [36] The responses to the Peace Note were negative: The Times of London headlined “German Peace Move”; Clemenceau dubbed the plan “a peace against France”. Only the Emperor Karl supported the plan. In Germany, Hindenburg and Ludendorff were in the driving seats and they considered that victory was in sight. The peace plan was sidelined.

The background to the Papal peace note was of course the carnage of the preceding year, that had prompted other initiatives. The Emperor Karl had succeeded to the aged Franz Josef who died that November, 1916, the same month that Woodrow Wilson was re-elected to the US Presidency on an isolationist ticket. Wilson proceeded to invite the belligerents to state their war aims. In December, Berlin proposed a peace, which was rejected as a “duplicitous war ruse” by the allies. [37] In early 1917, with food supplies increasingly scarce, Karl made overtures to the allies via his wife’s brother, Prince Sixtus of Bourbon. But his initiative infuriated Berlin and revealed Austria’s war weariness to the allies.[38] Later, in November, Lord Lansdowne sent a letter to The Daily Telegraph on November 29, calling for a negotiated settlement with Germany. He had sent the latter to the Cabinet a year previously and it had been immediately rejected. The public’s reaction was no different this time. “We are not going to lose this war, he wrote, but its prolongation will spell ruin for the civilised world, and an infinite addition to the load of human suffering which already weighs upon it…We do not desire the annihilation of Germany as a great power … We do not seek to impose upon her people any form of government other than that of their own choice… We have no desire to deny Germany her place among the great commercial communities of the world ».[39] Sir William Robertson, who had come up through the ranks to become Chief of the Imperial General Staff, ( his mother had written to him as a young man, that “I would rather bury you than see you in a red coat), [40] replied: « Quite frankly, and at the same time quite respectfully, I can only say I am surprised that the question should be asked. The idea had not before entered my head that any member of His Majesty’s Government had a doubt on the matter (of victory). »

The one common feature shared by these peace initiatives was the concern to end the war by negotiation, with the aim of achieving a settlement that could be accepted by all. Benedict’s way of expressing this in his seven point plan was to talk of substituting “the moral force of right…for the material force of arms”. This was to be achieved through international arbitration, common liberty of the seas, a renunciation of war indemnities, and an evacuation of occupied territories. Karl committed himself in letters to the Entente powers to the restoration of Alsace-Lorraine, Belgium, and Serbia, and to negotiations with Russia once a government was installed. [41] Lord Landsowne’s central point was for the Entente powers to accept Germany as a great power and thereby to work out a peace settlement agreeable to all. The precedent for such constructive statesmanship was the Treaty of Vienna, in which the victorious powers had incorporated France as one of the great powers, rather than isolating and punishing her. The reflex reactions over the coming decades of Prussia, Austria and Great Britain had been to seek to contain France, whenever its old demons were thought to be stirring again. Gradually, old habits died away: France and Great Britain were allies in the Crimean War; and France thwarted Hapsburg designs in Italy in the 1860s. The turning point came in 1870 with France’s defeat, the coronation of the new Emperor of Germany in Versailles, the stiff indemnities imposed on France, and the absorption by the new Germany of Alsace-Lorraine. The new European hegemon was now Germany. The way that the victors of the 1914-1918 war dealt with Germany was to punish it as the architect of the war, impose a punitive indemnity, de-militarise it, reject the Austrian popular vote for entry into Germany, and to deprive it of territories to the east and the west. The allies tried punitive diplomacy; their reward was Hitler.

Winston Churchill, reminiscing after the war of 1939-1945, observed that “”I am of the opinion that if the allies at the peace table at Versailles had not imagined that sweeping away of long-established dynasties was a form of progress, there would have been no Hitler”. [42] In view of the British experience of opening the old constitution to a wider suffrage in 1918, this statement is clearly identifiable as favouring the path of evolution over revolution, in which previous symbols of unity are thrown out in the course of struggles to impose new ideals and institutions. Dominant among these was Woodrow Wilson’s commitment to national self-determination as the key to the liberation of the peoples from the yoke of monarchical government. The one empire most directly effected was the Hapsburg domains. The Hapsburg ruling family was adamantly opposed to making nationality the defining characteristic of a political system. To Karl, Gordon Brook-Shephard has written, “the idea of nationalism based on language was unacceptable, and this was the basis for his opposition to an “Anschluss” of German Austria to Germany. In the Emperor’s view, Austria could never be defined in terms of Germanism. It was not confined to one language, to one ancestry”. [43]The Hapsburg realm was a multi-national monarchy, and stood or fell on that basis. The Hapsburgs fell not because their monarchy was incompatible with nationality, but rather because the progressive forces pushing for the monarchy’s dissolution considered nationality to be the exclusive criterion for legitimate authority. The people should decide. For the same reason, the Papacy-the sole institution which in effect spoke for the European interest in the First World War-was sidelined.

Who was to blame?

The task confronting the peacemakers at Versailles was formidable. Unlike at the Congress of Vienna in 1814-15, the three key leaders-Clemenceau, Lloyd George and Woodrow Wilson- were answerable to national electorates. It is true that Viscount Castlereagh, Great Britain’s plenipotentiary, was answerable to a jealous parliament, but he did not have to deal with mass political parties, a media baying for revenge, and millions of aggrieved families. All three leaders believed, along with the publics they represented, that the German state had been guilty in launching Europe and the world into war. All three leaders faced a world where the war had exacerbated nationalisms, feeding demands for revolution, territorial changes, revenge and compensation. Four empires disappeared in the conflagration. New states emerged, whose boundaries and populations had to be settled in one way or another. Differences between the three allies were pronounced enough, without the defeated states being present. Germany, Austria, Bulgaria, Turkey and Russia were not invited. This made the achievement of an enduring pan-European settlement unattainable.

For Clemenceau, the prime problem of the peace settlement was how to secure France against a future German aggression. For all the disagreements with “les Anglo-Saxons”, Clemenceau’s chief aim was to secure a permanent alliance with both the US and the UK. Lloyd George presided over a victorious country, that was now indebted to the USA, to the Commonwealth and to France. Its interest was in a stable and prosperous Europe. Hence, it shared with France the dilemma of wanting to punish Germany, but also to see it politically stable and economically prosperous. Woodrow Wilson’s high ideals of a “new world order” aroused high hopes in Germany for a just peace, but the Republicans, hostile to foreign entanglements, took control of both houses of Congress in the mid-term November 1918 elections, even before the peace conference had opened at Versailles in January 1919. A US priority was to achieve a stable and prosperous Europe that would be capable of repaying its debts. It was also to make the self-determination of the peoples, open diplomacy, and the practice of a collective diplomacy within the framework of a League of Nations the governing principles of a new Europe. But French security concerns clashed with the principle of self-determination: the German-Austrian vote for inclusion in the new Germany was brushed aside, and large minority German populations were incorporated in the territory of Poland and Czeckoslovakia; the main decisions by the Big Three were reached in secrecy; and the League of Nations was allowed no military of its own. The new peace depended on the behaviour of the states, but without the participation of the United States-where the Congress voted against the Treaty; without the participation of the Soviet Union; and with the eventual participation of a Germany whose population was almost unanimous that Versailles was a victor’s diktat.

This was the thesis presented by John Maynard Keynes’ in his famous pamphlet, The Economic Consequences of the Peace, published first in 1919. In it, Keynes condemned the French and British leaders for imposing a Carthaginian peace on the Central powers. Imposing such a peace, he maintained, was bound to fail. Wilson’s intuition had been essentially right: his Fourteen Points “brought healing to the wounds of the ancient parent of his civilization and lay for us the foundations of the future”. [44] Yes, the German people, Keynes wrote, had overturned the foundations on which the Europeans had lived and built, but the British and French leaders were completing the ruin. There could be no lasting peace built on reparations, debts should be forgiven, and Germany should be given a central role and stake in the Europe that had to be created for prosperity to return. Who was to blame for this failure? Keynes had no doubt: it was Clemenceau who shaped the outcome of the conference more than anyone else. The French leader conceived of European history as a “perpetual prize fight”, in which France had won this last round, and had to prepare against the day when Germany would once again “hurl at France her greater numbers, her superior resources and technical skill. [45] The allied leaders, Keynes wrote, paid no attention to the fundamental issue which was the economic rehabilitation of Europe. They were preoccupied with other concerns-“Clemenceau to crush the economic life of his enemy, Lloyd George to do a deal and bring home something that would pass muster for a week, the President to do nothing that was not just and right”. “Reparation was their main excursion into the economic field, and they settled it as a matter of theology, of politics, of electoral chicane, from every point of view except that of the economic future of the States whose destiny they were handling”.[46]

The book had an immediate success, particularly in the Anglophone world, where it helped to turn US opinion against the treaties , and contributed to the perception in British public opinion that Germany had been treated unfairly. But it received short shrift in France, starting with a report submitted in March 1919 to the French Senate by noted French historians, and entitled “Les origines et les responsabilités de la grande guerre”.[47] The judgement was unequivocal: “the war was premeditated by the Central Powers” which deliberately nullified conciliatory proposals advanced by the Entente Powers, “and rendered their efforts to avoid war totally ineffective”. Keynes’ passionate advocacy to treat Germany as a partner in a new peace for Europe was answered later by Ethiénne Mantoux in his best known book, The Carthaginian Peace, or the Economic Consequences of Mr. Keynes published two years after it was completed and one year after his death in 1945. Mantoux maintained that Germany should have had to pay for the whole damage caused by the First World War. He showed that Keynes’ estimates of future production of coal, iron and steel proved to be false. Keynes, he wrote, had argued that Germany would be unable to pay the 2 billion marks reparations for the next 30 years, but he rubbished that claim by demonstrating that German rearmament spending was seven times as much as that figure in each year between 1933 and 1939. More recent historians have tended to side with Mantoux: in his book, Does Conquest Pay? The Exploitation of Occupied Industrial Societies, Peter Liberman has written that the French view “that Germany could pay and only lacked the requisite will”, has “gained support from recent historical research”. [48]

The German war guilt clause found its way into the treaty in the form of Article 231. This was the opening paragraph in the section in the treaty on reparations. It read: “The Allied and Associated Governments affirm and Germany accepts the responsibility of Germany and her allies for causing all the loss and damage to which the Allied and Associated Governments and their nationals have been subjected as a consequence of the war imposed upon them by the aggression of Germany and her allies.» Germany in short was solely responsible for the start of the war. The thesis had no hope of surviving in Germany, whose population considered the war more than justified by the hostile intent of its neighbours; whose armies had been triumphant in the east in the course of 1917-18, and whose troops stood on foreign soil when the armistice was declared in November 1918. The great majority of Germans refused to accept the reality of their defeat, and were ready to believe the idea that the country had been “stabbed in the back” by malevolent forces-social democrats, weak-kneed Catholics, gullible democrats and Jews. The fact that 100,000 Jews served in the German military, that 70,000 fought in the front line, that 12,000 were killed in action, and that 18,000 won the Iron Cross did not alter the drumbeat of anti-semitism in Germany during and after the First World War. Nor was anti-semitism curtailed by the fact that the German wartime economy was run by a Jew, Walter von Rathenau; that Fritz Haber, a Nobel prize in chemistry, supervised the programme for the creation of poison gas, was Jewish; that some of the most eminent scholars in Germany, most notably Albert Einstein, were Jews. Anti-semitism was given a shot in the arm by the publication in 1920 of the Protocol of the Elders of Zion, a forgery which purported to show that Jews were out to run the world. The Protocol was soon debunked as a fraud, but won official support with Hitler’s ascension to power in 1933, and continues to circulate in anti-semitic circles, notably informing the content of Article 22 of the Hamas Charter.

Germany’s Foreign Ministry instead promoted the thesis that the war was not the fault of one nation but the result of the breakdown in international relations. The historiographical debate about who was guilty in launching the war was thus defined very early on,even prior to the opening phases of the Versailles discussions. At one end of the spectrum stand historians who blame one country or the other, mostly Germany, but also France, Great Britain and Russia; at the other end of the spectrum stand the historians who maintain that the failure lay in the structure and nature of the European diplomatic and state system. The importance of this debate may be measured by the fact that it fed into the post-1945 efforts to create a more lasting European peace. It was best expressed in August 1943 by Jean Monnet, later to become known as “père Europe”, who stated in his capacity as de Gaulle’s Minister of Armaments that: “ “There will be no peace in Europe if the States are reconstituted on the basis of national sovereignty, with all that that entails in terms of prestige politics and economic protectionism. The countries of Europe are too small to guarantee their peoples the prosperity that modern conditions make possible and consequently necessary. Prosperity for the States of Europe and the social developments that must go with it will only be possible if they form a federation or a “European entity” that makes them into a common economic unit. » [49]. War could only be banished by suppressing its cause, the national states.

This was not of course the intent of the German Foreign Ministry. Rather its purpose was to counter what its authors regarded as allied propaganda, and to justify Germany’s diplomacy in the lead up to 1914. The person who set up the organization- The Centre for the Study of the Causes of the War- was a Major Alfred von Wegerer. His organization was part of a wider network, centering around the Foreign Ministry-indicating the importance attached to the war guilt issue by the administrations of the Weimar Republic. There was a special section of the Foreign Ministry devoted to the question, the War Guilt Section; the Working Committee of German Associations; and a Parliamentary Committee of Enquiry. An initial publication, Is Germany Guilty? was published in the last moments of negotiations, before the government decided to accept the Treaty on 28 June 1919. The War Guilt section was set up on 21 July 1919; it had three editors, and its output was the 40 volumes of Die Grosse Politik der Europäischen Kabinette 1922-27, which became the standard work of reference for the German view of the First World War. Von Wegerer’s job was to operate at arms length to the government and provide financial support for sympathetic historians, mainly to be found in the United States of the 1920s, rather than in the Weimar Republic where many historians did not wish to be associated in any way with the “stab in the back” theory. A recipient of such funds was Harry Elmer Barnes, then a reputed historian who argued in his 1926 book, The Genesis of the World War, that Germany and Austria-Hungary were the victims of a Franco-Russian plot. [50] His view influenced generations of his readers, though at the time, Bernadotte Schmitt, the American historian, questioned Barnes’ on the grounds that it was Germany who “put the (European) system to the test in July 1914. Because the test failed, she (Germany) is not entitled to claim that no responsibility attaches to her”. [51]

Concluding remarks.

The fundamental question facing Europe in 1918 was how to lay the foundations for a durable peace. It was not who was or was not guilty. But that was the focus on which the public cast its attention. There were other failings too: the Japanese left the negotiations, convinced that the western powers did not wish to recognize the equality of races, as the Japanese delegation had suggested; the Chinese delegation left the conference in fury at not receiving back the peninsula of Kiaochow, followed by an outbreak of virulent anti-western nationalism in China and the foundation of the Chinese communist party; German speakers in Austria, Poland and Czechoslovakia considered with reason that the Treaty’s decisions on frontiers flouted the much heralded principle of national self-determination; the French nation did not achieve the security craved for; Great Britain found itself again at war in August 1939 most reluctantly, and despite the tremendous blood-letting among the British aristocracy, still with considerable influence in the affairs of state. But the Versailles treaty was not the failure its enemies made it out to be. It is difficult to imagine any circumstances in which Germany and Russia could have participated adirectly in the treaty negotiations; the allies could scarcely agree among themselves, other than on the broad principle that Germany was guilty. They could not agree on reparations, which by the early 1930s had been cancelled or shelved. The Versailles Treaty left the German economy in tact, as became evident in subsequent decades. Where the treaty failed was to reconcile the desire to punish Germany and the urgent need to stabilise Europe. It also failed to lay the foundations for a viable financial system. And the guilt clause, redundant as it was by 1933, provided Hitler with the political oxygen to get to office, and then to take over absolute power as Führer.

The stage was thus set for the most callosal of conflicts, between, on the one hand, the residue of the old Christian Europe, now in uneasy alliance with the heirs to the French revolution; and the new national socialist Europe, predicated as Adolf Hitler is quoted as saying, on nothing else than the implementation of the politics of biology.

[1John R. Schindler Disaster on the Drina: The Austro-Hungarian Army in Serbia, 1914, War in History, Volume 9, No 2, April 2002, pp. 159-195

[2] Hew Strachan, The First World War, London, Simon and Schuster, 2003, p. 59.

[3] Quoted in Alistair Horne, The Price of Glory, London, Penguins, 1993 ed. p. 221.

[4] Statistics of the Military Effort of the British Empire during the Great War, 1914-1920, London, HMSO, 1922, p.253.

[5] Strachan, p.133.

[6] С. Г. Нелипович Восточно-Прусская операция 1914 года. Saarbrücken, LAP Lambert Academic Publishing, 2012. pp. 57–58

[7] Cited in Ian Kershaw, To Hell and Back : Europe, 1914-1949, London, Penguins, 2016. p.46.

[8] Otto Liman von Sanders, Chief of the German Military Mission, Five Years in Turkey, 1927, pp.39-40.

[9] Strachan, p.57.

[10] Kershaw, p. 57.

[11] Max Hastings, Catastrophe : Europe Goes to War 1914,London William Collins,2013. p.495.

[12] Hastings, p. 553.

[13] Spencer C. Tucker, Laura Matysek Wood,; Justin D Murphy, The European Powers in the First World War: an Encyclopedia, Taylor & Francis. 1999. pp.150_152.

[14] Keegan, p.268.

[15] Strachan, p.120.

[16] Strachan, p.183.

[17] Keegan, p.321.

[18] John M. Taylor, » Audacious Cruise of the Emden”, The Quarterly Journal of Military History. 19 (4) Summer 2007: 38–47).

[19] Keegan, p.328.

[20] C.J.Hayes, A Brief History of the Great War, New York, MacMillans, p.276.

[21] G.W.L. Nicholson, The Canadian Expeditionary Force, Ottowa, The Queen’s Printer, 1962, p. 243.

[22] Keegan, pp.315-316. [22] A.J.P. Taylor, The First World War: An Illustrated History, London, Hamish Hamilton, p.148.

[23] Ibid. p.148.

[24] Hastings p.199.

[25] I grew up into my teens in the 1950s, when my father was still well alive, had started the war in 1914 as a second lieutenant, and ended it as a major. He had nearly four years of fighting experience, compared to only one year in the second World War due to the fact that he was already considered too old. Hence, for me, the First World War is much closer through his transmitted memories than is the second.

[26] See Klaus Pint, Die ökonomischen Aspekte vpn Friedrich Neumann’s Mitteleuropa und dessen Wirkung, Institut für Geschichte, Graz, 2009. Also, Friedrich Neumann, Mitteleuropa, Band 4, Köln, 1964.

[27] P.C.Kent and J.Pollard, (eds) Papal Diplomacy in the Modern Age, New Uork, 1994

[28] Keegan, p.63.

[29] Keegan pp.450-451.

[30] Jean-Jacques Becker, L’Année 14 Paris: Armand Colin, 2004, p.98.

[31],Peter C. Kent, John F. Pollard, Papal Diplomacy in the Modern Age, Westport, Prager, 1994, p.13.

[32] Terry Philpot, World War I’s Pope Benedict XV and the pursuit of peace, [32] National Catholic Reporter, July 19, 2014.

[33] John F. Pollard, The Unknown Pope: Benedict XV (1914-1922) and the Pursuit of Peace, London, Chapman, 2000. p.112.

[34] Ibid p.86

[35] Ibid p. 112.

[36] Ibid. pp. 123-128.

[37] Alexander Lanoszka; Michael A. Hunzeker , “Why The First War lasted so long », The Washington Post, November 11 2018. That may have been the case; but it is also credible that the allies needed to show each other maximum determination in order to dispel any afterthought that one or the other may be backsliding.

[38] Keegan, p.345.

[39] « Co-ordination of Allies War Aims”, Letter from Lord Lansdowne, Daily Telegraph, 29 November 1917, p.5.

[40] Victor Bonham-Carter, Soldier True:the Life and Times of Field-Marshal Sir William Robertson. London: Frederick Muller, 1963. p5.

[41] The incident is presented in Charles Coulombe , Blessed Charles of Austria: A Holy Emperor and his Legacy, nNorth Carolina, TAN Books, 2020, pp171-185.

[42] Martin Gilbert, Road to Victory: Winston S. Churchill, 1941-45, p.114.

[43] Gordon Brook-Shepherd, The Last Hapsburg, Weidenfeld & Nicholson, 1968, 316-317.

[44] John Maynard Keynes, The Economic Consequences of the Peace, London, MacMillan, 1919, pp. 34-35.

[45] Ibid pp.34-35.

[46] Ibid pp.211-212.

[47] Rapport Presenté à la conférence des préliminaires de paix par la commission des responsabilités des auteurs de la guerre et sanctions : Conférence des préliminaires de paix. 29 Mars 1919.

[48] Peter Liberman, Does Conquest Pay ? The Exploitation of Occupied Industrial Societies,Princeton, Princeton University Press, p. 89.

[49] Cited by Leonardo Veneziani, in “Day of Europe”, Vocal Europe, 09/05/2018.

[50] Holger Herwig, “Clio Deceived : Patriotic Self-Censorship in Germany after the Great War, “ International Security, vol.12, No 2. pp. 5-44.

[51] Quoted in Annika Mombauer, The Origins of the First World War, London, Pearson, 2002, p.103.